As usual, listen here to a Chrome AI-generated podcast type playback of this article:

The original non-AI generated article follows below:

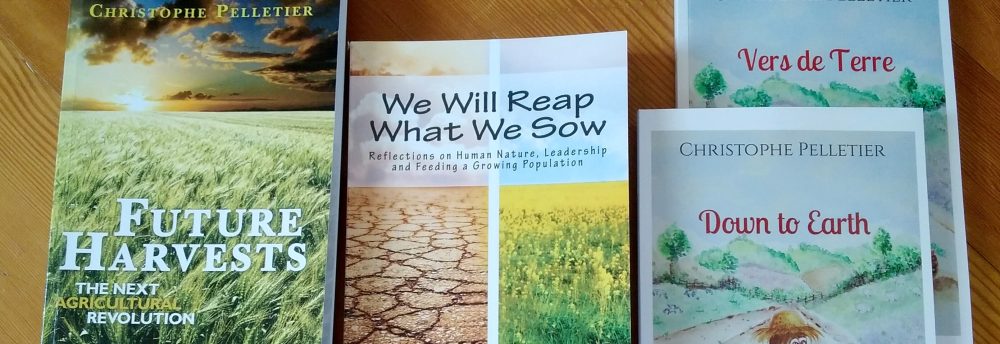

The issue of food and climate is ongoing. There are many different views about what is perceived as damaging and what is perceived as sensible. The debate tends to be polarized, mostly by both extremes. I discussed that topic a long time ago in a chapter of my second book (We Will Reap What We Sow, 2012) and all I can say is that the answer is far from simple. Of course, some people think it is, and their answer aligns with their dogma. That is not necessarily helpful. Food is a complex issue. First, food choices are rarely rational and nutrition usually does not play a prominent role, even though everybody does a great job of rationalizing their choices. The thing is that people choose what they eat mostly based on emotional and psychological aspects. It can be societal issues. It can be what they have been used to eat since childhood. It can be cultural. It can even be a political statement or the expression of their belonging to a particular socioeconomic group. Every possible reason is out there.

Protein hype

The debate around animal versus plant is really mostly focused on protein. In my opinion, this is already the first flaw. Both animal products and plant products contain much more nutrients than just protein. Even within the protein category, different animal products and plant products present rather different profiles of amino acids, and essential amino acids in particular. Yet, the essential amino acid profile is what defines the quality of a protein. Unfortunately, the quality aspect of protein is often overlooked, which is quite a serious mistake. The focus is on quantity, hence the current protein hype that brings food suppliers come with all sorts of high-protein products. It is just marketing and has little to do with rational nutrition. If the focus was on rationality, it would be clear that, at least in developed countries, people eat on average already enough protein, generally speaking. They do not need more. They might need better protein, though. The best diet is one that provides the needed amount of protein, no more and no less. Eating more protein results in two drawbacks. One is that the excess calories (because people from developed countries already consume more calories than they really need) from protein end up adding to body fat, so it might not be such a healthy strategy after all. The second drawback is that the excess nitrogen (protein is the only nutrient group providing nitrogen) provided by a diet too rich in protein is going to be excreted through the kidneys in the urine, so basically eating too much protein leads to pee your wallet away in the toilet, so to speak.

Plant or animal: a misplaced feud?

All the surveys that I read show the same: the overwhelming majority of people consider animal products an essential part of a healthy nutrition. Only a couple of percents of the population from developed countries consider that people should not eat meat. That is their choice. Such a point of view is not based on biology. It is a doctrine, not a diet. The question is how much protein a person should eat, and how much from animal origin. This is a much healthier debate. There are different opinions about that one, but accepting the obvious -it is not either/or but and/and- allows for more constructive conversations.

Another absurdity of the polarization on the type of protein is that often the debate is presented as if there were only two categories of people: pure carnivores and vegans, and nothing in between. Wrong! Even meat lovers eat some foods of plant origin, too. Regular people, aka the overwhelming silent majority of consumers, eat a mix of animal products and plant products. This special blend has a name. It is called a meal! Here is the interesting part of a healthy diet: it combines all sorts of ingredients that all bring their share of nutrients to the body. They complement each other. Some bring essential amino acids, others bring essential fatty acids, others bring fiber, others bring minerals, vitamins, antioxidants and other micronutrients.

The entire human digestive tract -including teeth- shows that we have evolved into omnivores. Like it or not, this is the biological reality. Humans eat a bit of everything. The term flexitarian is just a hollow neologism created purely for marketing purposes to make believe there is another category and lure people. It did not get much traction for the simple reason that it is just hot air. People are not stupid. Omnivore is what counts for more than 95% of the population in developed countries. I may insist much on the developed country distinction in this article. The reason is simple: there are many people on Earth who unfortunately eat only what they can afford, not what would be best for them. They do not have that luxury. If and when, thanks to better economic prospects, they can afford more choice, be assured that they will increase their consumption of animal products. That has been the same pattern everywhere in the world before.

The talk about hybrid products

During the past couple of decades Some people have put a lot of effort into trying to convince us to give up meat by making all sorts of bogus claims about replacing all cows by 2030. Reality begged to differ. The cows are not going away. There is no reason why they should. Production systems have changed and they work towards reducing the issues linked to animal production, but animal products are here to stay. Actually, all forecasts from serious sources show that consumption of animal products will increase globally, mostly as a result of the growing world population. People in developing countries also want access to meat, dairy and eggs. And let’s face it, in these countries, they do not have the money to buy the novel tech foods, so forget those. That category is for the affluent westerners. And it has not done well. Plant-based fake meat is a failure. Just look at Beyond Meat. Only a few plant-based foods companies are doing fine and they are not in the investor-led tech sector. Since the tech plant-based fake meat cannot survive on its own, a new strategy has arisen. The idea is to bring people to eat less meat by replacing a part of the meat by protein from legumes (soybean and pea mostly). If you look at it, it comes down to incorporate the fake meat into real meat. As such, why not?

The only regions where they are now trying to sell their products is the EU and the UK, not so much as 100% plant-based fake meat, but as hybrid products. The danger of this approach is that it tends to be sneaky and people are starting to notice. It is interesting to note that this approach is mostly a European one. Opposite to that, in North America, the fake meat market is dead. Period. To my knowledge, the EU is the only region that so skillfully sabotages its food security, in particular in the sector of animal production. They do it partly for political reasons under pressure of environmental organizations and also partly because, I hate to say, EU leaders suffer from some sort of a moral superiority complex that leads them to impose standards that undermine the future of farming in the EU while they seem to think that the rest of the world would adopt those standards because, well, Europe says so. Good luck with that! The thing is that the EU is not even self-sufficient in plant protein and their regulations on those productions also weaken their farmers’ competitive position.

So, the tech companies, after realizing that they could not beat meat, have chosen a different approach. Let’s join the meat and have hybrid products. I understand the thinking, but I wonder if this might not have the opposite effects of what the plant-based protein industry and some EU politicians trying to force onto people think it will achieve. Let’s have a look at potential problems.

First problem is that hybrid products are tricky to identify, as their labeling and packaging mimic the pure meat products they want to replace. This sneaky -if not weaselly- approach might become more difficult now that the EU has passed legislation on labeling of non-meat products trying to pretend to be meat. I have seen -and tasted- this deception first hand.

An unpleasant discovery

Last year, I was visiting my family in France. As usual when I visit, they ask me to do the cooking. One of the meals was beef patties they had bought at a local supermarket, or so I thought. It was a product from France’s leading beef producer, so I did not pay much attention but as I was preparing the meal, I felt something was wrong. The color was strange. It was an unusual beautiful red. I have never seen such red beef because beef is never that color. Anyway, since my parents had bought it, I thought it had to be the real thing and shrugged it off. Then, in the frying pan, those patties were not behaving like normal beef patties, either. They would not brown nicely like the way I am used to. Further, they were rather bouncy and rubbery in texture. I could not really press them. Then, I served them and I had the same weird feeling when I stated to bite and chew on them. The texture was odd. Anyway, we had our meal. I was not very happy because it did not taste great but we moved on. It is only later that I found a journalist’s report about that beef brand, explaining that they also sold hybrid patties nicely colored with beat juice, and I will bet my shirt that it is exactly what I ate that day. This year, I visited my family again and I went to the supermarket. What I saw really disturbed me. The supermarket’s was selling its own label “Haché de Boeuf” (best translation would be “ground beef”) next to trays of “Haché Pur Boeuf” (Ground pure beef). There it was! I grabbed one of each to look at the labels. The Haché de Boeuf was not just beef. It contained 25% (a quarter!) pea protein isolate, plus a lengthy list of all sorts of weird ingredients, the types used in the plant-based fake meat. The Haché Pur Boeuf was indeed all beef with nothing weird added. I do not have a problem with supermarkets selling any kind of product they want but I have a huge problem with them selling something under a name that does not give any indication of ingredients that do not belong in what the name of the product suggests. Put it anyway you want, but Haché de Boeuf translates as ground beef and nothing else. Haché means ground and boeuf means beef. Haché de Boeuf should be beef and nothing else. Actually, they have done the opposite and created a new name for the original real thing. Ground beef is not longer Haché de Boeuf. It has become Haché Pur Boeuf. Of course, the average shopper can’t tell the difference between ground beef and ground beef unless they would become suspicious of everything, which they clearly should do. If you do not pay close attention, there is a chance that you are taking home something that is not what you think. I would not trust that supermarket anymore. What else do they sell under misleading names? Should the shopper become a food inspector? Well, perhaps yes.

Another example, also from France, of such a lack of transparency happens in bakeries. Due to the high price of butter, many bakers have switched to hybrid fat (butter mixed with fat of plant origin) products for croissants and other pastries simply because the production cost is lower than with only butter. In France, there are two categories of croissants: ” croissant au beurre” (croissant made with butter) and just “croissant” (made with fat of plant origin) which are the cheaper version. The problem is that the croissants made with the hybrid fat are labeled -and sold- in bakeries as “croissants au beurre”. It is perfectly legal but consumers are left to believe that the only fat source used is butter, and that is not the case. Almost all consumers are actually even unaware that these hybrid fat products exist. Those croissants are in between the two categories but sold for the price of the better croissant. Although legal, this feels like deception and that is not good for trust in food.

But, as I mentioned, the new EU legislation should prevent that in the future. Though, it is funny -and ironic- to see the reaction of the alt-protein sector to this new legislation. Of course, as you would expect, they find it unfair and unjustified. Everyone is a victim, and they in particular. They consider that fake imitations should be called meat or chicken or fish. When challenged, they reply by saying that people are not stupid (which I said earlier, too) and they claim that the people buying the fake products are well aware that it is not the real thing. So, if people know the difference, why wanting to call it like the real product it pretends to be? That does not make any sense, but there is a simple reason. The fake meat producers and their advocates know quite well that animal products have appeal and that theirs do not. Maybe, they should think about why that is. If people know the difference and it is not the same thing, why don’t they show real creativity and invent a brand new word for their products and fully differentiate themselves. The difference is what creates a loyal tribe. A few thousand years ago, the ones who developed tofu and tempeh created these very words, which did not exist before. Why can’t all those ego-inflated food tech people who were about to revolutionize food and agriculture and save the planet cannot think of something as simple as an original name, or is it because they could not really develop an original product, either, and cannot do any better than imitate something that has existed since the dawn of time instead? Frankly, that is their problem.

Hybrid products are not just in France. A few supermarket chains from The Netherlands and in Germany have also pledged to sell at least 60% of plant-based products. It has already been noticed that they also present confusing packaging that does not clearly inform the consumers about the true nature of the products. They are also already accused of green washing. From what I gather, the idea behind the claim of 60% (yes, why that magic number?) would be to meet GHG targets. I write this in the conditional and you should read it that way, too. I have not been able to find a reliable source to confirm this. Nonetheless, I do not think 60% is difficult to achieve considering all the products of plant origin they already sell. Here, think of fruit, vegetables, bread, legumes, rice, pasta and so on. I am sure you can also make up a list of plant-based products sold in supermarkets. That makes sense because the diet of the normal person I mentioned at the beginning of this article, being an omnivore, also eats at least 60% of foods that are of plant origin, next to the animal products. Further, having a product listed does not mean that it sells. The best example, especially with plant-based products in mind, is Beyond Meat. They were listed in all the restaurants, from global fast-food chains to independent eateries. They were listed in all supermarket chains, too. Yet, they masterfully flopped. Of course, the retailers do not present the 60% in that angle. They prefer to go along with the dogma of their politicians in power, and come with the usual meat-blaming rhetoric because it is risk-free and sounds so virtuous. So, will they label hybrid products clearly or will they deceive their customers? That is their choice. Trust has seriously eroded in about everything, and if they choose deception and misinformation, it will backfire on them. The winners in such a situation would be the specialized butcher shops, dairy shops and fishmongers. They are the ones with a quality-minded concept. That said, quality varies greatly and let’s face it, there are also products of animal origin that are of poor quality sold in stores. I could name quite a few that I would not touch with a 10-foot pole.

EU food producers and retailers must be careful about transparency. Consumers defense organizations are powerful in that part of the world. Messing around with the consumers will not do anyone any good. What a total violation of the idea of transparency and trust this is! It is actually ironic, as supermarkets over there are so keen to tell times and times over how transparent they are and how much they cherish creating trust. Generally speaking, if you go to France, my advice is to buy your meat at a butcher’s shop or on one of the many markets. The quality of many products I have seen in the supermarkets in France this past visit has disappointed me beyond my imagination. They really need to fix that situation.

Can hybrid products succeed?

Of course they can, but not with the same approach and attitude as the plant-based fake imitations used in the recent past. If they keep the same approach, the result will be the same. People are now well aware of tech foods and they associate them with ultraprocessed foods. So, my advice here would be, do not sell tech processed foods. Sell good old-fashioned wholesome foods. Sell healthy nutrition instead of tech “prowess”. It is cheaper, it requires less investment and no intellectual property for which all the failing food tech companies have been suing each other lately. In food, to succeed, short and long term, you have to offer nutritious foods.

When it comes to protein, legumes are in the spotlight. In their natural form,they offer protein but also carbohydrates, fats and fiber (which belongs to carbs), along with a whole range of micronutrients. Sooner or later, the question of whether building factories using energy to deconstruct the bean or the pea to extract just the 20-25% protein it contains is really worth it or sensible will arise. It is a good thing that farm animals are here to upcycle the by-products. Would it not make more sense to use the whole bean/pea as a wholesome unprocessed ingredient into a recipe with other wholesome ingredients? Be assured that this question will arise sooner or later, too. Ultraprocessed is out and ultraprocessed foods producers have a very hard time regaining trust from consumers, with one interesting exception: the meat-loving beefcakes on social media that hate fake meat products and yet love the protein powders that are probably made in the same plants as where the tech fake meat source their protein isolates. There are not that many companies producing those products, so just connect the dots!

At the beginning of the tech fake meat hype, a number of companies, mostly meat companies ventured in hybrid territory. It does not seem to have had much appeal. The question that producers need to ask themselves is: do people really want to that kind of blend? Do they want a highly processed product like a protein isolate invisibly mixed with a basic processed product like ground meat? When it comes to value for money, it is clear that quality will be a decisive criterion. Is hybrid the best or will it be the worst of both worlds? Success will depend on the consumers’ answer to that question. To succeed, the perceived quality of hybrid products will have to be at least the same as the perceived quality of the original animal product. If not, it will be an uphill battle. If the quality is perceived as at least equal, hybrid products will succeed, at least some will. And there might be some potential irony about this. If people like these products and want more of them, it might actually increase indirectly their consumption of animal products. I recently had a conversation with the CEO of a company that sells mushroom-based products that are used in hybrid products and he was claiming to be successful and mentioned that the growth of these hybrid infused meat products were actually strongly outpacing sales of pure plant-based category. It sounds that the main casualty of hybrid products might very well be the plant-based foods, not the animal products.

In 2019, I had posted two articles on this blog about what I saw ahead for both animal products and for plant-based products. I believe that my conclusions of then have materialized rather well. As far as hybrid products are concerned, I believe that quality will be key. I also believe that they will need to make ingredients recognizable to the eye. The impossibility for the consumer to see clearly what they eat will lead to failure. A long list of “mysterious” ingredients will do the same. Of course, the worst of the worst would be to keep trying to deceive consumers by not being transparent. The latter will kill your business in less time than it takes to flip a burger.

I also believe that if the conversation about animal and plant protein becomes more intelligent than during the last decade, people will think more about complementarity than opposing the two categories. In the UK, some organizations have recently launched a campaign to encourage people to eat more beans and other legumes. I believe that it is a good idea. However, beans may have a couple of inconveniences to overcome. If you use dry beans, it takes a bit of time to soak and cook them. It is not that complicated or particularly time consuming but I expect that to be a hindrance. The other possibility is to use canned beans. It is quite convenient. It is easy to store. It is already cooked and ready to use. The problem here is to make canned beans sexy again. It has an old-fashioned image and that might work against them. And then, there is the issue of flatulence. It is not the most exciting topic but it needs to be mentioned. There is a simple solution to this problem: add a little bit of baking soda in the beans.

Personally, next to meat, I am an avid consumer of beans, peas, chickpeas and lentils. Since I cook, I make a lot of dishes with beans, most of which also contain meat, but I also make salads, soups or dips with them. I love to cook and I enjoy making old traditional recipes from many parts of the world. From Chili con Carne to Snert (Dutch pea soup), Cassoulet (French bean and sausage, or even duck confit), Saucisses aux lentilles (sausages and lentilles), Couscous (welcome chickpeas!) or Feijoada (Brazilian dish pork and black beans), you name it and it comes on my table. Here you can see me with a big bag of beans on the thumbnail of a video I published in the past about meat consumption.

This is the beauty about cooking from scratch. You control what you put on your plate and then you eat simple, nutritious and wholesome foods. When you do that, there is a good chance that you will not suffer from micronutrient deficiency, which cannot be said of ultraprocessed products. Unfortunately, many people think that cooking is complicated and time-consuming. I know and understand the perception, but since I have been cooking since my student years about every day of my life -and I have had quite a busy one- I can assure you that it is a lot simpler and quicker than often believed. For instance, one of my household’s favorites is the veggie soup (yes, plants!) that I make with 6 to 8 different sorts of vegetables. I make a big pot at once and we have soup for almost a week. This shows that it doesn’t need to be a daily chore. Of course, convenience foods companies will not encourage people to cook, as it takes some of their business -and their nice margins- away. Convenience is not cheap.

And of course, last but not least, the price at the point of sale will be a decisive element of success or failure. The more processed the product will be, the cheaper it will have to be. Consumers will follow a simple thinking: plant foods and therefore hybrid products should be cheaper than meat. The value for money will be key. If consumers think that they are buying processed plants for the price of meat, they will not buy it. If in doubt, take a look at what it did to tech fake meat. People will not switch from pure meat if it is more expensive or even for the same price. If the price is the same, they will stick to the “real” or “pure” (pick you adjective) product. It is just simple psychology.

Next week: Communication: Humanity and Authenticity make for Effective Conversations

Copyright 2025 – Christophe Pelletier – The Food Futurist – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

Will the UK face an economic crisis or a recession? Maybe but maybe not. That would not be the first time and eventually the UK has always recovered. I do not see why this would be any different. I remember when Black Wednesday took place in 1992. By then, I was in charge of the UK market for a Dutch poultry processing plant. The UK was the main destination of breast fillets, our most expensive product and overnight the company turn-over was headed to a major nosedive. The Brexit excitement of today feels nothing like the panic of then. Regardless of how stressful it was, the Black Wednesday situation delivered some good lessons in term of business strategy that I am sure would be beneficial in today’s situation.

Will the UK face an economic crisis or a recession? Maybe but maybe not. That would not be the first time and eventually the UK has always recovered. I do not see why this would be any different. I remember when Black Wednesday took place in 1992. By then, I was in charge of the UK market for a Dutch poultry processing plant. The UK was the main destination of breast fillets, our most expensive product and overnight the company turn-over was headed to a major nosedive. The Brexit excitement of today feels nothing like the panic of then. Regardless of how stressful it was, the Black Wednesday situation delivered some good lessons in term of business strategy that I am sure would be beneficial in today’s situation.

This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water.

This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water.