Everyone who works in agriculture and food knows that there are about one billion people on Earth suffering from hunger. The temptation to think that the cause is a lack of food production is great, but it does not reflect reality. Quite a few serious organizations and personalities claim that one Earth is not enough to feed nine billion people by 2050. Some claim that we would need two Earths. Others even go as far as mentioning the need for three, and even four, of our blue planet.

There are two possibilities with such statements.

If they are true, then humanity has a problem, because there is only one Earth, and we will not get a second one. In such a case, the only way for supply and demand to get in balance is a reduction of the world population. This could happen through famine, disease and/or wars. Since in such a scenario there is a maximum to the world population, once this number is reached, there must be a constant elimination of the couple of billion people too many, through one of the means just mentioned. This is not a particularly happy thought.

On the other hand, if such statements are erroneous, there is hope to feed the increasing world population with one Earth.

Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong.

Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong.

Out of the six billion who do not suffer hunger, it is estimated that one billion is overweight, a part of which, mostly in the USA, is obese. They clearly ingest more calories than they need. Purely theoretically, if those were to share the excess food they consume with the ones who have too little, the billion hungry people would have about enough. This means that today there is already enough food available to feed seven billion people.

Another interesting factor is waste. According to the FAO, about 40% of all the food produced is lost and wasted. In rich countries, most of the waste takes place at supermarkets, restaurants and households level. People simply throw away food. In developing countries, the waste takes place mostly post-harvest. The food does not even reach the market. The food is spoiled because of a lack of proper storage facilities and logistics. The food ends up rotting, contaminated with mould or is eaten by vermin. To fix the problem, the FAO estimates the cost to improve infrastructure at US$ 80 billion. This is less than the amount the EU just made available to bail out Ireland. What to say of the US$ 3.3 trillion that the US Federal Reserve lent to banks to alleviate the financial crisis? Of course, it will be impossible to achieve an absolute zero waste, but if we were to achieve 10%, this will feed many people. I have heard the statement that if post-harvest losses were eliminated in India, the country would be fully food secure. Per 100 tons of production, 40% wastage means that only 60 tons are available for consumers. By reducing waste from 40% down to 10%, there would be 90 tons available. This represents an increase of food available by 50%! Since we could already feed seven billion with the 40% waste, reducing wastage to 10% would allow feeding 10.5 billion people.

There are also many debates about whether we should eat meat or not. The nutritional need for protein is easily covered with 30 kg of meat per capita per year. I had shown in an earlier article that if Western consumers were consuming just what they need instead of eating superfluous volumes (very tasty and enjoyable, though), it would free meat to feed 1.4 billion people the yearly individual 30 kg. In China, the average meat consumption is already up to 50 kg per capita per year. The consumption is very unevenly distributed, but this is the average. Cutting 20 kg per capita over a population of 1.5 billion would free meat for the nutritional needs of an additional one billion people.

The other area of potential is Africa. The FAO estimates that the area of arable land that is not exploited is about 700 million hectares. This is about the size of Australia. To simplify and get an idea of the potential, we can calculate what it means in wheat equivalent. With the assumption that wheat yields would be the same as the current African average, a low 1.5 tons per hectare, this adds up to 1.05 billion tons of wheat. Since a person needs about one million calories per year, and there are about 3,000 calories in a kg of wheat, one ton of wheat can feed three people, the 1.05 billion tons of wheat can feed more than 3 billion people. Normally, there would a crop rotation of at least two harvests per hectare. With proper investment and financing, farms should be able to reach easily the US average of 3 tons of wheat per hectare. Clearly, this performance could be achieved with traditional techniques and good quality seeds. This is not even about high-tech or GMOs. This tremendous potential of Africa is why China, India and Arab countries are very active developing farming there. They did the math. This scenario also shows that Africa can easily become a strong net exporter of food. In this case, the world map of food looks very different. Without Africa being able to produce large amount of foods, the prospects for food security in Asia and the Middle East are a bit bleak. They can depend only on Western Europe, Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, North and South America, and with Australia to a lesser extent. With Africa as a net food exporter, the world map looks a lot more balanced, East-West as well as North-South. Sea routes from Africa with the Arabic Peninsula, the Persian Gulf, and farther away with India and China create a much safer feeling of food security for the countries in those regions. For Africa itself, it may change the relations between Sub-Saharan country and the Maghreb countries. This in turns changes the type of relationship that the Maghreb may have with Europe, by creating more economic activities to the South. Africa’s success –or failure- will affect the whole world.

With the above, everyone can develop further assumptions, but these calculations show that this one Earth can produce enough food to cover the needs of between 12 and 15 billion people. It almost sounds impossible to believe, yet these numbers are not even ambitious. I have not even taken into account that in 2009, 25% of the corn produced in the USA was destined to feed cars, not people, via ethanol production, and that number is expected to grow to about one-third for 2010. The potential is even higher when one considers that a large part of the US corn goes into soft drinks, while it could be used to produce tortillas, with a side glass of water, a much healthier alternative.

That said, if the potential for food production supply looks adequate, actually producing it may not be as easy. The human factor, especially through politics and leadership, will be crucial to succeed.

One would ask why there is hunger if we can produce so much food. The answer is simple. Hunger is not just about food production, it is about poverty. People are hungry because they do not have money to buy food. They do not have money because they do not earn enough, as they have low paying jobs or simply no jobs at all. By developing the economy in these regions, people would get better wages. They could afford more food. The demand would drive the development of food production. Agricultural development would then be a normal and natural activity. Trying to develop agriculture if the locals cannot buy the food cannot work. Recently the FAO estimated that two-thirds of the world’s malnourished live in only seven countries: China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Ethiopia and Congo. These are countries where most of the population is poor, and most of which lives in rural areas. The other proof that hunger is not only a consequence of low food self-sufficiency can be found in two agricultural exports behemoths: Brazil and the USA. In the latter, a recent survey carried out by Hormel Foods, the deli producer, shows that 28% of Americans struggle to get enough money to buy food, or they know someone who struggles. Last year, the USDA had estimated at 14.6% the percentage of US households that do not have enough food on the table. Food will find the money and vice-versa. If Bill Gates decided to move to the poorest and most food insecure place in the world, and would fancy a lobster, I am sure that someone would manage to find him one and deliver it within reasonable short notice.

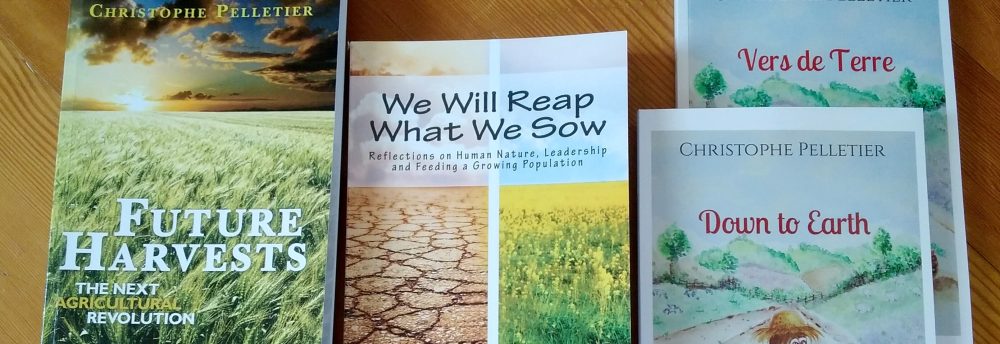

My book, Future Harvests, investigates the possible scenarios to increase food supply and meet the demand at the horizon 2050.

Copyright 2010 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong.

Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong.