Over the past year, there has been quite a bit of talk about alternative proteins and in particularly the so-called plant-based products. Let’s face it; the hype (which I already mentioned in my previous article about cow farts) has been very well organized to inflate what has been going on in the markets. Probably, it is part of the culture of “disruptive” tech start-ups. They are quite good at using social media, making the wildest claims about how they are all going to change the world. When it comes to food, what will happen before you know it is that there will be no need for farms anymore. Just take a look at Sci-Fi movies and it is there! Yeah, right. The problem, well one of the problems, I have with this is that I have heard it before. Actually, I heard similar things before today’s disruptors were even born. In the 1970s, after the Apollo programs, we would not eat traditional foods anymore. No, our meals were going to be contained in pills. Yeah, right. It did not happen. Around the turn of the century, we had the new economy, not just a new economy, but the new economy thanks to dotcoms and internet. The old economy was history, for ever. Yeah, remind me how the dotcom bubble burst and how a few years later the old economy demonstrated it was still alive and kicking through its Great Recession. More recently, we all heard that Amazon was going to “disrupt” retail so much that brick and mortar retailers were going to go down. Yes, Wal-Mart was finished. Not. Actually, Wal-Mart is doing quite fine and for a simple reason. Solid businesses follow what is happening in their markets and they make the proper changes. And that is exactly what happened with most retailers around the world. They went digital and they started to sell online and deliver to customers. Similarly, e-books were going to kill paper books and online diplomas were to mean the end of universities. Well, paper books and bookstores certainly have had difficult times but they did a nice comeback. And universities are still very much alive, while the MOOCs are the ones that seem to have left the building. There is more to life than digital versions of the original products and services. Silicon Valley and co suffer of a good dose of hubris. Maybe, they should attend to that before it might become their demise some day.

The thing with so-called disruption is that the only businesses that actually get disrupted (in the true sense of the word, not the trendy sense) are the ones that are asleep and not paying attention. They would have died anyway. The businesses that are awake adapt. That is pretty basic business stuff. Since I got started about disruption, I would just say that I do not like that term because as I mentioned earlier, it is taken in its new trendy meaning, which really means nothing else than innovation and change, but those words are too mundane. I will agree that disruption sounds more dangerous. It makes you feel like a rebel and a threat. Yeah, isn’t it something that we all fantasize over when we are kids, being a tough rebel?

Let me be clear, I am all for innovation and for having implemented changes in a number of businesses; I know that it is a constant of life, but I am interested in change that is a natural evolution toward real improvement. I am much less interested in gadgets and made-up hypes that have as primary goal to fill the pockets of a few. I guess I am not easily impressed and it is not because something is the flavor of the month that I forget about my good old well rooted-in critical mind.

So let’s go back to the plant-based protein products. First, they are nothing new, even if the current business owners want to make us believe that their products are jewels of high-tech. If so, how come that so many companies are going in the very same market on such short notice? The answer is simple, those products are not difficult to replicate. Plant-based alternatives are not new and they have been around for a couple of millennia for some of them such as tofu, koftas and falafel. Soy burgers have been around since the 1930s, really becoming mainstream in the 1980s.

What makes the current ones so different? Honestly, not that much at all. So why the hype? For two reasons mostly. One is the use of social media which are great tools to inflate whatever message you have and that so many people are willing to relay for you without even knowing what they are talking about. But it makes them feel part of the tribe for as long as it lasts. The other one is that this time big money has been invested in those companies and wants to cash in big, so they are putting their resources and their relationships at work to reach that goal. When your product is the talk of the day every day in every media outlets, it sounds like it has taken over the world. It’s just good old-fashioned smoke and mirror tactics. Just find out which billionaires and venture capitalists have put money in these companies and you will realize that it is a beautiful exercise in investor-driven social-media-led push marketing for a production-driven commodity business. Here in Canada, we have seen the exact same pattern with cannabis stocks after the country legalized cannabis sales a year ago. A lot of hype was aimed at having money buying stocks so that the founders could make great capital gains. It almost sounded that because of the new legislation, every Canadian would splurge on pot, either breathing it or eating and drinking it. Yeah right. As if making something legal would inevitably turn people into addicts. Pot users could already find all they needed before the legalization, as is the case everywhere in the world. So, the market was already well defined. Nonetheless, cannabis stocks shoot up like rockets because when greed kicks in people get gullible. Actually, I suspect greed is as addictive as drugs. Early investors sold on time with big fat capital gains and one year later, the share price of cannabis stocks are stagnating to low levels again. I expect something similar to happen with plant-based protein stocks. It is already kind of happening already, especially with Mr. Big Bucks-who-blames-cows-for-farting-for personal-gain having sold his Beyond Meat stocks quite conveniently before they started to stumble.

What is ahead for plant-based meat alternatives?

The first thing to think about is what those products are. What do they mimic? They mimic beef burgers mostly and sausages to some extent. They do not look as much like fresh beef burgers as they do the basic sad frozen ones. My point here is that they look like cheap commodities. And the thing about looking like a commodity is that it makes your product a commodity. The fact that so many other companies can replicate similar product in such a short period of time just confirms that it is a commodity and certainly not a niche specialty. The first rule for a niche to resist competition is that the product/service is quite difficult to replicate and match. Clearly, that basic first rule does not apply here. The only product that escapes the commoditization risk is the plant-based shrimp. Shrimps are a commodity but there is such a shortage of seafood compared with demand, shrimp prices are high and should remain high for a while. Imitation shrimp profit margins should be more resilient.

The second thing that comes to mind is the price of plant-based protein products. I can give here only what I can see in the stores around where I live in Canada. The regular price for a half-pound package of plant-based burger is CAD7.99 (that’s CAD15.98 per lbs). That is about twice the regular price of a pound of ground beef, but I can buy ground beef on ad for CAD3.99 and even from time to time CAD2.99. The price gap is quite big, and that will have to change if the plant-based burgers want to gain substantial market share. I believe this is starting to happen with a Canadian brand of plant-based burgers advertising last week at CAD4.99 for half a pound (that’s down 40% from the regular price) and this week the American brand was for sale at CAD5.99 for half a pound (25% down from regular price). Price drop has to be compensated by additional volumes to achieve profit margin goals. Here a word of advice to the CEO of that American company who expressed not being interested in hearing about his competitors (weird statement but what the heck, who can you fear when you think you are God): pay attention to your competitors because they want to take a slice of the pie and possibly your entire pie with it; their growth will not be your growth. Prices start to show some action and the big meat companies who are about to enter have not made their mark yet. That is going to be fun, because the hype created this idea that the market potential is huge and they are ramping up to produce large volumes. The meat and poultry industry has a long history of overcapacity, oversupply and profit margin destruction. I suspect that they will bring some of that experience in the plant-based imitation meat. I think things are going to be interesting. Prices are going to go down and raw materials (soybeans and peas) probably will increase in price to match demand. Prices down plus costs up is the perfect equation for squeezed margins, both for plant-based and animal protein by the way. The ones who will benefit the most are the crop farmers to some extent, but mostly the producers of protein isolates (the raw material used to produce the imitation burgers), the highest margin will be in the health and wellness protein supplement sector, basic low-cost plant-based burgers should well because of attractive pricing, and perhaps the consumers to some extent.

But for consumers, a couple of other things will play a role. One of them is perception. Do they like the product? And with perception comes value. Will the perceived value be higher than the price gap between the imitation product and the original beef? Perception is not just about the product but also about the company. So far, producers are perceived as small start-ups, which is often translated by consumers as small, brave and pure. If they knew actually how much big money and Big Agriculture is behind, I wonder how that would affect perception, and this time will come because, after all, are we not in a transparent food system by now as all food corporation like to claim?

Plant-based burgers producers brag about the many places where they have their products offered to consumers, but being on the menu of a restaurant is not the same as having consumers actually buying it, but they present it as it were, and stock markets react accordingly. There has been a lot of buying out of curiosity because of the hefty social-media hype but the perception is a different story. I have read many reviews and I cannot see any significant trend one way or another. There are those who praise the product and there those who trash it. Online reviews are notorious for the amount of fake reviews and I am sure there are plenty of those on both sides for obvious hidden agenda reasons. Fact is however that only after a few weeks in the trial, the Canadian restaurant chain Tim Hortons removed the plant-based burgers from its locations except in British Columbia and Ontario. Plant-based burgers “opponents” mention a number of characteristics they do not like: high price, highly processed products, high sodium content, long list of ingredients and some ingredients they can hardly read and have no idea what they are. I will make a mention of sodium content here. In the stores around my place, I can find only one Canadian brand and one American brand. I compared the sodium content of their products with regular potato chips. Here are the numbers: potato chips 230 mg sodium for 50 g product, Canadian brand imitation burger 540 mg sodium for 113 g (that’s 239 mg Na per 50 g of product – slightly more than the potato chips!!); and American imitation burger 340 mg sodium for 113 g product (that’s 150 mg Na per 50 g of product – that’s two thirds of the potato chips sodium content). Why don’t they add sodium and let people decide how much salt they want to put on their burger? I know the answer to that question but I will let you figure it out. I rarely buy potato chips but when I do, I buy the half sodium ones, which are lower in sodium than even the American imitation burger. You can make the same comparison with what you find in your stores and draw your own conclusions.

The third thing to expect is the push back from the animal protein producers, and that has already started. There are many fights about definition of meat and dairy. Let’s face it, the producers of plant-based products know very well that if they advertise to carnivores with an herbivore undertone, it will not work very well, so they try to make their products look more carnivore-like. There are also fights about environmental claims about benefits of plant-based vs. animal protein, many of them unsubstantiated. Altogether, plant-based products keep many lawyers busy. The fact that there many legal battles does not bode well. In France, there is an old saying: “better a poor agreement than a good lawsuit”. It will be interesting to see how that will translate for the future of plant-based. Of course, bold statements such as the plant-based sector bring the US meat and dairy sectors to complete collapse by 2030 is not a great way to make friends. Plus, please refer to the beginning of my article for why existing businesses are much more resilient that newcomers tend to think, but hey they have to attract investors’ money after all so no claim is bold enough.

Regardless of all the fights and arguments, the market will decide and as usual markets will decide on price and value. The value will be about money but also about health and environmental aspects as well. The question, though, will be whether the price differential will be worth it. I indicated prices earlier. In terms of potential market share, from reliable sources I have found it sounds like plant-based might represent 2% of the protein market in 2020 and perhaps reach 10% in 2030 in the USA. To gain more market share, plant-based imitation meat products would probably need to be offered at half the price they are now at least, everything remaining equal, further. If they don’t adjust their pricing, they will be happy to amount to 5%. Also and because the market could be crowded, plant-based protein producers will have to differentiate themselves from the competition and the characteristics that I mentioned earlier will weigh more, and so will the use of GMO ingredients or not play a role. Of course, there is a good chance that, as usual with the food industry, they all will try to differentiate themselves the same way, thus shifting their universe a bit to the right but all offering more or less the same.

If going plant-based protein is more efficient than meat, and it is because it removes one layer in the food chain, then it would only be logical that plant-based be cheaper both in price and in cost, but it’s not because unfortunately most “future of food” products are not meant to cater the hungry poor. So, here is another price to keep in mind: the price for a pound of cooked beans, peas, chickpeas and lentils is around CAD0.99 per pound. If you wish to switch to vegetarian, using the wholesome grain in the first place without industrial processing is quite a financially attractive proposition and I believe that they will be winners for the future from a global perspective, not just the US market with its First World solutions for First World problems. The thing is that the First World does not seem to know about cooking anymore, in spite of trendy flashy kitchens. The market will also decide which businesses succeed and which ones fail. Start-ups little gods or not, the percentage of failure remains the same as ever: about 75% of businesses do not make it longer than 3 years. Often, the reason is ignoring competition and not understanding that it takes much more than production methods to win over customers. As for the animal protein sector, what will be the consequences? I have written a few articles about the subject (do a search on meat and protein in the search bar on the right hand side of this page to get the list of articles). I will simply finish with a chart that show past consumption and estimates of animal protein consumption for the future based on UN FAO data and you will see that animal protein are really not expected to suffer from competition of alternative protein sources.

There will be plenty of room for everybody: animal protein, plant protein, processed or wholesome, as well as traditional products and all sorts of innovative alternatives. There is no need for cockiness, belligerent statements and inexact claims. The markets and future economics will sort out the winners. In the end, we all have to work together and the key will be about producing and consuming sustainably. Production systems will change. That is normal. And it is going to take the efforts of all 10 billion people and their food choices, not just from food producers.

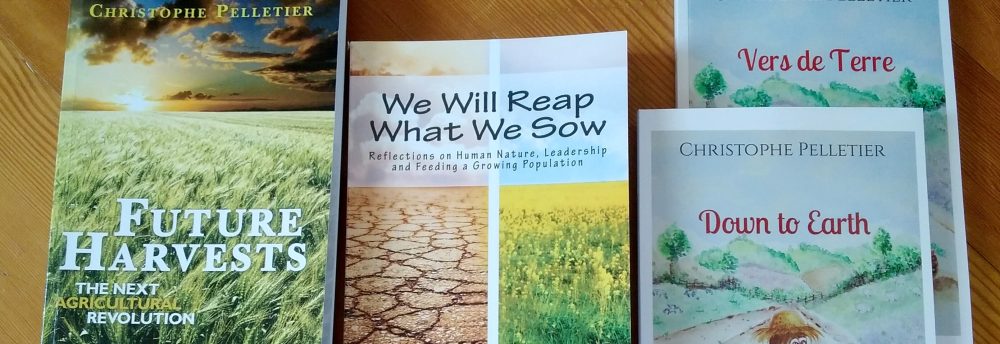

Copyright 2019 – Christophe Pelletier – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

It focuses on the sectors of fashion, furniture, and electronics, or more precisely on what they call the wegwerpmaatschappij, or in English the throw away society, being all about products that have a cheap price tag but do not last and end up in no time in the landfills. The article hints toward moving away from fast fashion and fast furniture and at looking at buying better products of much higher quality. It is interesting to notice that while food and agriculture are often presented as the source of all evils, they are not mentioned in this article. Yet, there certainly is a lot to say about food waste, overconsumption, crappy, unnecessary and useless products. Anyway, I will let you read it and as there is a chance you cannot read Dutch, just translate the page with Google and you will find the content.

It focuses on the sectors of fashion, furniture, and electronics, or more precisely on what they call the wegwerpmaatschappij, or in English the throw away society, being all about products that have a cheap price tag but do not last and end up in no time in the landfills. The article hints toward moving away from fast fashion and fast furniture and at looking at buying better products of much higher quality. It is interesting to notice that while food and agriculture are often presented as the source of all evils, they are not mentioned in this article. Yet, there certainly is a lot to say about food waste, overconsumption, crappy, unnecessary and useless products. Anyway, I will let you read it and as there is a chance you cannot read Dutch, just translate the page with Google and you will find the content. It describes a difference of opinion between the Minister of Finance and the Minister for Ecological Transition. The latter criticizes Black Friday, presenting it as a symbol of hyperconsumption. He is not wrong although there are also people who take advantage of the Black Friday discounts and offers to buy products that they actually need. Even though we buy and consume way more than we should, and therefore waste of lot of resources to produce these items, sometimes purchases are about necessary stuff. There is a risk in brushing everything with the same brush. The Minister of Economy is, of course focused on the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and does not fancy the idea of refraining from buying stuff (the essence of GDP) all the much. Anyway, they bicker at each other. In the conversation, other aspects are brought in, such as online sales versus brick-and-mortar stores. Online sales are a regular pet peeve of French governments, and Amazon in particular, or anything that has to do with American corporations. Overconsumption is overconsumption, and cheap crap is cheap crap, regardless of where you buy it. Nonetheless, this is an interesting article to read, as it shows the struggle of how to reconcile economy and environment. Both the Dutch and the French articles touch the concept of quantitative growth vs. qualitative growth, and the need of always enough vs. always more, about which I wrote earlier on this blog.

It describes a difference of opinion between the Minister of Finance and the Minister for Ecological Transition. The latter criticizes Black Friday, presenting it as a symbol of hyperconsumption. He is not wrong although there are also people who take advantage of the Black Friday discounts and offers to buy products that they actually need. Even though we buy and consume way more than we should, and therefore waste of lot of resources to produce these items, sometimes purchases are about necessary stuff. There is a risk in brushing everything with the same brush. The Minister of Economy is, of course focused on the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) and does not fancy the idea of refraining from buying stuff (the essence of GDP) all the much. Anyway, they bicker at each other. In the conversation, other aspects are brought in, such as online sales versus brick-and-mortar stores. Online sales are a regular pet peeve of French governments, and Amazon in particular, or anything that has to do with American corporations. Overconsumption is overconsumption, and cheap crap is cheap crap, regardless of where you buy it. Nonetheless, this is an interesting article to read, as it shows the struggle of how to reconcile economy and environment. Both the Dutch and the French articles touch the concept of quantitative growth vs. qualitative growth, and the need of always enough vs. always more, about which I wrote earlier on this blog.