Looking at the future of food and farming goes far beyond agriculture. It comes down to looking at the future of humankind. Balancing future supply and demand of food is an exercise that includes many disciplines and dimensions, probably more so than any other human economic activity. Anything that affects life and its level of prosperity must be taken into account. Feeding the world is not just a matter of production. Of course, the ability to produce and to keep producing enough food is paramount, but there is more to it than that. The consumption side is just as important. Demand will depend on the diet, which also depends on how much money people have available to pay for food.

Total future food demand is a combination of which foods and food groups people in the various regions of the world will buy and eat. This is a function of demographic, economic, cultural, religious and ethical factors. If future demand is about consuming according to the nutritional needs of a human being, clearly the situation will be different than if people demand twice as many calories and protein as the actual nutritional needs. The relative share of animal products in the total diet will also change the situation in terms of production and of production systems. Food production must adjust to the demand and do its best to meet it, but not at all costs. Therefore, it is essential to optimize food production at the global level so that the largest quantity of food can be produced at the lowest environmental cost. At the local level, production depends of course on natural conditions, but also on economic, political and cultural conditions as well. This may be the most profound change that we must deal with: feeding the world of the future is a global exercise. As more and more people worldwide have more and more money to spend on food, demand is now global, and therefore production plans must also be global. The times of producing food simply for the own people and exporting surpluses is over. Markets will now react to any event that will affect production or consumption somewhere else. Borders do not make this shift in thinking easy. It is always tempting to think that having one’s house in order is enough, but it is not. What happens in other countries on the other side of the world will affect us just as well. Why is that? Just one word to explain it: markets. There used to be a time, not so distant when if there was a drought in Russia, China or Brazil, markets would not react as strongly, and anyway not so much in the media, as we have seen over the past few years. This was the case because only a minority of the world was consuming large quantities and that minority did not have competition. Now the competition is wide open. Markets will keep reacting on this and the relative price levels of various foods will influence how much of what is consumed and where. We will see eating habits change because of this economical aspect of food supply.

At the same time, food production is also adapting to a changing environment, and to face its future challenges. The amount of new developments in technology, access to information and knowledge and in decision-making tools is amazing. Innovation is flourishing everywhere to solve environmental issues, to cope with new energy and water situations. The dominant themes are the reduction waste of all sorts, as well food as agricultural inputs and by-products, and the prevention of the release of harmful contaminants. Innovation is developing towards better and more efficient systems that must ensure the future continuity of food production and, at the same time, keeping food affordable for consumers. Interestingly enough, many innovations that will be useful for agriculture do not originate from the food sector. Food producers will need to be curious and look beyond the field to prepare for the farming of the future.

Clearly, the number of factors affecting both consumption and supply are many. To add to the complexity, many of these factors are not of an agricultural nature. Many of them originate from the population, its activities and its needs for all sorts of goods. I mentioned earlier that what happens in one region affects others, but the natural resources markets, such as energy, metals and minerals, that must meet demand for non-food consumer goods also affects agriculture and its production costs. Although many see rising costs first as a threat, I tend to welcome them, as they always stimulate innovative solutions to increase efficiency and reduce waste. Two examples show that it works. One is the car market in the USA that shifted from gas-guzzlers to high gas mileage vehicles since gas at the pump became much more expensive than it was only 5 years ago. The second one is food markets. Had you heard as much about food prices, food security or food waste before the food price hikes of 2008 and 2012?

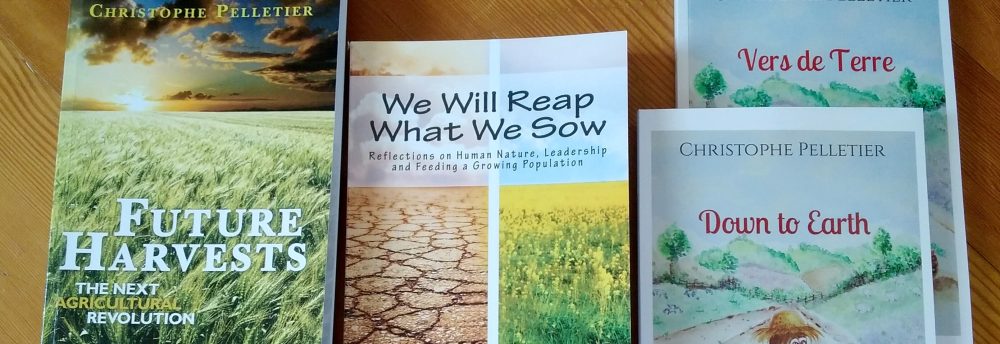

In my work, I always try to make my clients and audiences aware of how everything that has to do with food is interconnected with many other sectors, and how economic, demographic and political events are linked to food security or how they might affect it in the future. That is an underlying them in my books.

Even, within the food and farming sectors, organizations do not realize enough how their future will be influenced by other food productions and vice-versa. I always get reactions of surprise at the magnitude of the interconnection and the interdependence with these factors, and how they affect their activities indirectly. It is a normal reaction, as most people tend to focus on what has a direct connection with their activities. After all, that is why I do what I do: to help them see and decipher this complexity, and understand what actions to take to adapt and prosper. I never shy away from show the complexity. My audience needs to get a flavor of the any dimensions and many layers involved. However, I always take a practical approach and show them that complexity is not the same as complicated. Deconstructing the complexity actually works well to show the many levels of actions there are. It helps my clients connect the dots between their activities and what will affect them and how. It gives them a level of confidence in how to deal with the future and take action. I also like to warn against oversimplifying, which is another tendency that I observe from time to time. The mainstream media is rather good at that. But I also get questions that sound like those who ask hope that I have a magic wand and will be able to give them a foolproof recipe for success. That simply does not exist. If preparing the future were easy, nobody would even talk about it. It would be done. It it was easy, I guess many of the organizations that have been involved in agricultural development and food aid for decades would have already succeeded, and they would not exist anymore. Yet, they still have to keep up with their work.

Feeding the world is work in progress. Developing the right actions is complex, but not as complicated as it sounds. However, the true difficulty is in the execution, and in particular bringing other stakeholders with different agendas and different views on board to contribute to the success.

Copyright 2013 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

Every activity that pollutes without cleaning the contaminants is a negative externality. Everything that damages physically the environment and undermines the sustainability of food production is a negative externality. Every activity that depletes essential resources for the production of food is a negative externality. In this highly industrialized world, the consequences of economic and human activities, slowly add up. Nature’s resilience makes it possible for damage to remain unnoticed for quite some time. However, the ability of Nature to repair the damage shrinks, as the damage is continuous and exceeds Nature’s ability to cope with the problem. As the population increases, the level of human and economic activities intensifies further. There will come a time when Nature simply cannot handle the damage and repair it in a timely manner anymore. The buffer will be full. When this happens, the effect of negative externalities will manifest immediately, and it will include the cumulated damage over decades as well. It will feel like not paying the bills for a long time and then having all belongings repossessed. Humanity will feel stripped and highly vulnerable. The advisory services company KPMG published a report in 2012 stating that if companies had to pay for the environmental cost of their production, it would cost them an average 41% of their corporate earnings. These costs are currently not included in the pricing. That is how high negative externalities can be. Looking at it from the other way, companies would still deliver 59% of their current earnings. Repairing the damage and still generate profits shows that sustainability is financially achievable. On average, the profits would only be lower, but the impact would vary substantially between companies. Businesses that create high negative externalities will show much bigger drops in profits, than business that do the right thing. The only ones who would have to get over some disappointment would be Wall Street investors and all those who chase capital gains on company shares. The world could live with that. Investors should put their money only in companies that actually have a future.

Every activity that pollutes without cleaning the contaminants is a negative externality. Everything that damages physically the environment and undermines the sustainability of food production is a negative externality. Every activity that depletes essential resources for the production of food is a negative externality. In this highly industrialized world, the consequences of economic and human activities, slowly add up. Nature’s resilience makes it possible for damage to remain unnoticed for quite some time. However, the ability of Nature to repair the damage shrinks, as the damage is continuous and exceeds Nature’s ability to cope with the problem. As the population increases, the level of human and economic activities intensifies further. There will come a time when Nature simply cannot handle the damage and repair it in a timely manner anymore. The buffer will be full. When this happens, the effect of negative externalities will manifest immediately, and it will include the cumulated damage over decades as well. It will feel like not paying the bills for a long time and then having all belongings repossessed. Humanity will feel stripped and highly vulnerable. The advisory services company KPMG published a report in 2012 stating that if companies had to pay for the environmental cost of their production, it would cost them an average 41% of their corporate earnings. These costs are currently not included in the pricing. That is how high negative externalities can be. Looking at it from the other way, companies would still deliver 59% of their current earnings. Repairing the damage and still generate profits shows that sustainability is financially achievable. On average, the profits would only be lower, but the impact would vary substantially between companies. Businesses that create high negative externalities will show much bigger drops in profits, than business that do the right thing. The only ones who would have to get over some disappointment would be Wall Street investors and all those who chase capital gains on company shares. The world could live with that. Investors should put their money only in companies that actually have a future. A consequence of the specialization between crop farms and intensive animal farms is the rupture of the organic matter cycle. Large monoculture farms have suffered soil erosion because of a lack of organic matter, among other reasons. In soils, the presence of organic matter increases moisture retention, increases minerals retention and enhances the multiplication of microorganisms. All these characteristics disappear when the quantity of organic matter decreases. A solution to alleviate this problem is the practice of no-tillage together with leaving vegetal debris turn into organic matter to enrich the soil. This has helped restore the content of organic matter in the soil, although one can wonder if this practice has only positive effects. Tillage helps eliminating weeds. It also helps break the superficial structure of the soil, which can develop a hard crust, depending on the precipitations and the clay content of the soil. Possibly, in the future the use of superficial tillage could become the norm. Deep tillage, as it has been carried out when agriculture became mechanized, has the disadvantage of diluting the thin layer of organic matter in a much deepen layer of soil. This dilution seriously reduces the moisture and mineral retention capacity of soils, thus contributing to erosion as well, even in organic matter-rich soils.

A consequence of the specialization between crop farms and intensive animal farms is the rupture of the organic matter cycle. Large monoculture farms have suffered soil erosion because of a lack of organic matter, among other reasons. In soils, the presence of organic matter increases moisture retention, increases minerals retention and enhances the multiplication of microorganisms. All these characteristics disappear when the quantity of organic matter decreases. A solution to alleviate this problem is the practice of no-tillage together with leaving vegetal debris turn into organic matter to enrich the soil. This has helped restore the content of organic matter in the soil, although one can wonder if this practice has only positive effects. Tillage helps eliminating weeds. It also helps break the superficial structure of the soil, which can develop a hard crust, depending on the precipitations and the clay content of the soil. Possibly, in the future the use of superficial tillage could become the norm. Deep tillage, as it has been carried out when agriculture became mechanized, has the disadvantage of diluting the thin layer of organic matter in a much deepen layer of soil. This dilution seriously reduces the moisture and mineral retention capacity of soils, thus contributing to erosion as well, even in organic matter-rich soils. This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water.

This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water. For most customers, white eggs are perceived as being from intensive cage production, while brown eggs are perceived as being more “natural”. Everyone with knowledge of the industry knows that the color of the shell has nothing to do with the nutritional quality of the egg. The belief that the egg color indicates a difference persists, though.

For most customers, white eggs are perceived as being from intensive cage production, while brown eggs are perceived as being more “natural”. Everyone with knowledge of the industry knows that the color of the shell has nothing to do with the nutritional quality of the egg. The belief that the egg color indicates a difference persists, though. Of course, it would be interesting to imagine what people would eat if they were rational, and what impact on our food production this would have. A rational diet would follow proper nutritional recommendation, and to this extent would follow the same principles as those used in animal nutrition. However, this would not have to be as boring a diet as what animals are fed. A rational diet does not need to be a ration. After, the human genius that is cooking would help prepare delicious rational meals. It would be like having the best of both worlds. The emotional, social and hedonistic functions of food would remain. The key would be about balance and moderation. If people were eating rationally, there would not be any diet-related illnesses. There would not be obesity. There also would be a lot less food waste. This would improve the level of sustainability of agriculture.

Of course, it would be interesting to imagine what people would eat if they were rational, and what impact on our food production this would have. A rational diet would follow proper nutritional recommendation, and to this extent would follow the same principles as those used in animal nutrition. However, this would not have to be as boring a diet as what animals are fed. A rational diet does not need to be a ration. After, the human genius that is cooking would help prepare delicious rational meals. It would be like having the best of both worlds. The emotional, social and hedonistic functions of food would remain. The key would be about balance and moderation. If people were eating rationally, there would not be any diet-related illnesses. There would not be obesity. There also would be a lot less food waste. This would improve the level of sustainability of agriculture. Yet, with an increasing world population and the need for more food production, one can wonder whether agricultural subsidies really are a problem. History has shown that subsidies can be a very effective way of boosting production. For instance, subsidies have been a major element for the European Union to increase its agricultural production in the decades following WWII. To show how effectively money talks, you just need to see how financial incentives have made European vintners pull off vines, then replant them pretty much at the same place later. Subsidies have encouraged Spanish farmers to plant many more olive trees than the olive market needed. Subsidies work. When people are paid to do something, they usually do it quite willingly.

Yet, with an increasing world population and the need for more food production, one can wonder whether agricultural subsidies really are a problem. History has shown that subsidies can be a very effective way of boosting production. For instance, subsidies have been a major element for the European Union to increase its agricultural production in the decades following WWII. To show how effectively money talks, you just need to see how financial incentives have made European vintners pull off vines, then replant them pretty much at the same place later. Subsidies have encouraged Spanish farmers to plant many more olive trees than the olive market needed. Subsidies work. When people are paid to do something, they usually do it quite willingly. Since WWII, much progress has been made to increase food production, such as genetic improvement, production techniques and mechanization, use of fertilizers, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the development of animal nutrition, and of course government incentives. This has resulted in our ability to produce more efficiently and face a previous doubling of the world population. It has helped reduce costs and made food more affordable to more, although unfortunately not to all.

Since WWII, much progress has been made to increase food production, such as genetic improvement, production techniques and mechanization, use of fertilizers, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the development of animal nutrition, and of course government incentives. This has resulted in our ability to produce more efficiently and face a previous doubling of the world population. It has helped reduce costs and made food more affordable to more, although unfortunately not to all.