Over the past decades, agricultural subsidies have received an increasingly bad publicity, especially as a major part of the WTO Doha round of negotiations is aimed at removing them.

Yet, with an increasing world population and the need for more food production, one can wonder whether agricultural subsidies really are a problem. History has shown that subsidies can be a very effective way of boosting production. For instance, subsidies have been a major element for the European Union to increase its agricultural production in the decades following WWII. To show how effectively money talks, you just need to see how financial incentives have made European vintners pull off vines, then replant them pretty much at the same place later. Subsidies have encouraged Spanish farmers to plant many more olive trees than the olive market needed. Subsidies work. When people are paid to do something, they usually do it quite willingly.

Yet, with an increasing world population and the need for more food production, one can wonder whether agricultural subsidies really are a problem. History has shown that subsidies can be a very effective way of boosting production. For instance, subsidies have been a major element for the European Union to increase its agricultural production in the decades following WWII. To show how effectively money talks, you just need to see how financial incentives have made European vintners pull off vines, then replant them pretty much at the same place later. Subsidies have encouraged Spanish farmers to plant many more olive trees than the olive market needed. Subsidies work. When people are paid to do something, they usually do it quite willingly.

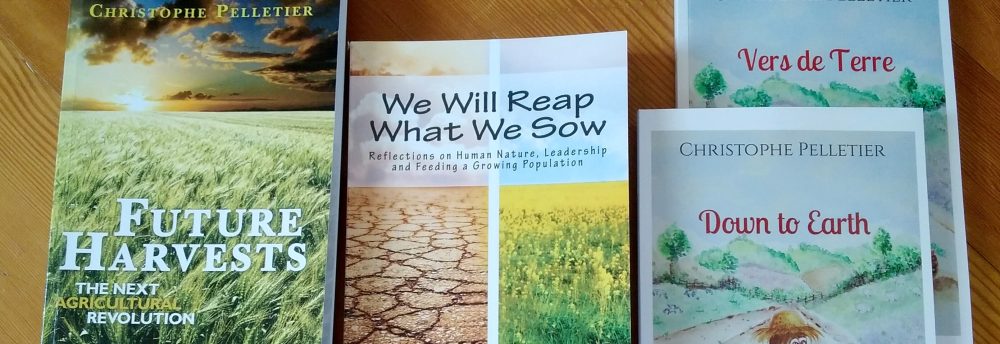

The true problem with subsidies is to have a cost-effective system. Subsidies must help produce what is needed. They are only a means and they must not become an end. Subsidies also need to deliver the right incentive to be effective. Too often, they have adverse effects because they do not encourage the right behaviour. An example of subsidy that seemed to aim at the right action and yet did not deliver proper results is the subsidy on agricultural inputs by the Indian government. They subsidize fertilizers with the idea that, this way, fertilizers would be more affordable for farmers and therefore the farmers would be able to increase their yields. As such, this is not a bad idea, but the practice showed a different outcome. Farmers with little or no money were still not able to buy enough fertilizers, and richer farmers just bought and used more fertilizer than necessary. The result has been an over fertilization in some areas and an insufficient fertilization in other regions, as I explained in more details in my book, Future Harvests.

For subsidies, too, quality must come before quantity.

Subsidies must be a part of a comprehensive plan towards the essential goal: feeding more people. They must be part of a market-driven approach, and they should not to entertain a production-driven system. Subsidies, or should I call them government support, take many forms and many names, from straight subsidies to grants, “market support mechanisms”, “export enhancement programs” or specific tax regime for farmers, etc… There is quite a bit of semantics involved. Perhaps the stigma on subsidies comes from their being granted by governments. Aren’t private investments just another type of subsidies? After all, that money aims at encouraging more production. The main difference is about the kind of return. Private investors look for a capital return, while governments look for a societal return.

A positive example of effective money incentive linked to a comprehensive approach that involved government and private companies is the rice production boost in Uganda (which I also present in Future Harvests). This effective policy helped increase production 2.5 times and turned Uganda from an importing rice country to a net exporter within 4 years!

I believe that the main bone of contention about subsidies is the competition on markets. Every player involved on world markets, either importers or exporters wants 1) to have the best conditions to compete against others and 2) wants to make conditions for others to compete as difficult as possible. The untold story is that many countries would like others to cut their subsidies while keeping (some of) their own. Only the competitor’s subsidies are unfair. Moreover, addressing subsidies is not enough. At the same time as subsidies, all import restrictions, such as anti-dumping tariffs or import duties should be looked at, as they are blatant attempts to skew the competitive positions.

The issue is not really aimed at developing a comprehensive plan to feed the world. The Doha round started in 2001, but since then, we have had the food riots of 2008 and the spectre of further food inflation. This, too, should be taken into account.

Considering how critical financing is for farmers, and that many farmers (more than half in the USA) need a second job to make ends meet, some form of financial support is generally very useful. Also, let’s not forget that we will need farmers for the future and agriculture needs to be an attractive profession if we want to have the people that we need to produce all the food!

Copyright 2010 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.