The path to feeding the growing world population and to preserve agriculture’s ability to provide adequate volumes is paved with many challenges. Leaders will have to show how to resolve the many issues food production is facing or will face in the coming decades, and how to create a viable future.

As the population increases, the need for energy increases, too. Oil reserves are finite and new oilfields are becoming more and more difficult and expensive to exploit. It is only logical that oil will become more and more expensive in the future. This will call for more fuel-efficient equipment and vehicles. At the same time, oil that is more expensive also means that the relative price for alternative energy sources will become more competitive. In March 2011, an analyst from the bank HSBC published a report announcing that oil will no longer be available in 2060. In its future projections, the International Energy Agency (IEA) describes our energy sources as more diverse than they are now. They also mention that oil will not be the main source of energy anymore. Natural gas will take over. We should expect some significant changes in the way agriculture uses energy, the type of machinery that farmers will use and how future logistics will be organized.

The change of economics in energy will affect fertilizers, too. Especially, the production of nitrogen fertilizers uses large amounts of fossil fuel, essentially natural gas. On average, half of the nitrogen spread on fields is lost because of leaching. We can expect the focus to be on efficiency and on strategies of applications that are more efficient. This is already happening with precision agriculture techniques. Next to this, the focus of the fertilizer industry should be on developing nitrogen fertilizers that are less sensitive to leaching. Imagine a nitrogen fertilizer that may cost twice the price of the current ones, but for which there is no loss. Farmers would use only half the quantities that they currently do. The money to spend would be the same, but the use of fossil fuel to produce the fertilizer would be much less. There would be an environmental advantage to do so.

In the area of environmental issues, climate change needs to be addressed more effectively than it has been so far. Regardless whether people believe in it, or believe it is caused by human activity or it is only a natural phenomenon, the number of severe climatic events is reason to consider counter measures, just in case. The debate should not be about whether climate change is real or not. It is not about who may be responsible for it. True leaders take care of their people, and in this case, they should at least come with scenarios, contingency plans and emergency preparedness plans. That is the least we must expect from those in position of power and responsibility. In this case, the saying “the failure of the preparation is the preparation of failure” takes all its meaning.

Linked to climate to some extent, and a precious resource in all cases, water needs to be managed properly and carefully. For instance, all major river systems in Asia depend on Himalayan glaciers. If the glaciers were to disappear, which is a possibility, the source of water that sustains 2.5 billion people would be depleted, even if water used for agriculture also comes from other sources, the monsoon especially. The consequences would be catastrophic. Further, as agriculture uses 70% of all fresh water resources, growing food production will require more efficient water usage techniques. The focus must be on efficiency and on reduction of waste of water resources. Such objectives will require substantial financial resources and solid planning.

In the area of waste, food losses must be reduced as much and as diligently as possible. The moral issue of food being thrown away by the wealthy is obvious. The wealthy are not just in developed countries. In emerging countries, similar behavior is appearing. It is interesting to know that the Indian government is considering fines for those who discard edible food. It is even more interesting to notice that in Western countries where the percentage of food thrown away is the highest, governments are not investigating this possibility of fines. The other food waste scandal is the post-harvest losses. The food is produced. It is edible, but because of a lack of proper infrastructure, it is left to rot. What a waste of seeds, land, water, money, labor and all other necessary inputs. I have mentioned this problem in previous articles, as I have shown that the financial return to fix the problem is actually high and quick. There is plenty of work in this area for leaders. The first step to succeed in this is to recognize that no organization can fix this on its own. There is a need for collaborative leadership, because all the stakeholders in the food chains must participate, and they all will reap the financial benefits of fixing post-harvest problems.

Food production is not a hobby. It is of the utmost importance for the stability and the prosperity of societies. Well-fed and happy people do not riot. The need to improve infrastructure and logistics is obvious. Food must be brought to those who need it. A proper transportation infrastructure is necessary. The choice of transportation methods has consequences for the cost of food supply, and for the environmental cost as well. Road transport is relatively expensive and produces the highest amounts of greenhouse gases. Rail transport is already much better, and barge transport even better. The distance between production areas and consumption centers also needs to be looked at, together with the efficiency of logistics. Optimization will be the name of the game. Completing the cycle of food and organic matter will become even more important than today, as the world population is expected to concentrate further into urban centers. As humans are at the end of the food chain, many nutrients and organic matter accumulates where the human settlements are. These nutrients, as well as the organic matter, will have to be brought back to the land. This is essential if we want to maintain soil fertility. As phosphates mines are gradually running out, sewage and manure are going to play a pivotal role in soil fertility management. The concentration of the population in urban centers, together with the change of economics in energy, will require a very different look on economic zoning, and in urban planning in particular.

Special attention will be necessary to inform and educate consumers to eat better. Overconsumption, and the health problems that result from it, is already becoming a time bomb. Overweight is not only a Western problem. The same trend is appearing in many developing countries as well. Overweight is on the rise all over the world. The number of obesity cases in China, and even in some African countries, is increasing. The cost of fixing health is high, and it will be even more so in countries with an aging population, as age-related ailment add up to eating-habits-related problems. Healthy societies are more productive and cost less to maintain.

As the economy grows, and wealth increases in more and more countries, diets are changing. Consumers shift from carbohydrate-based meals to a higher consumption of animal products, as well as fruit and vegetables. The “meat question” will not go away. Since it takes more than one kg of feed to produce one kg of animal product, increasing animal production puts even more pressure to produce the adequate volumes of food. The question that will arise is how many animals can we -or should we- keep to produce animal protein, and what species should they be? Levels of production, and of demand, will result in price trends that will regulate production volumes to some extent, but government intervention to set production and consumption quotas cannot be excluded, either.

Similar questions will arise about biofuel production, especially the type of biofuel produced. There will be debates about moral, economic, social and practical aspects of biofuels. The consequences on the price of food and animal feed are not negligible. The function of subsidies in the production of biofuels adds to this debate and there are strongly divergent points of view between the various stakeholders.

One of the most important issues in the discussion about feeding the increasing world population is food affordability. Producing more, and producing enough, is not enough. The food produced must be affordable, too. When this is not the case, people cannot eat, and this is the main reason for malnourishment. To make food affordable, food production must be efficient. The costs of production need to be kept under control to avoid either food inflation and/or farmers bankruptcies.

In agriculture, just like in any other human activity, money always talks. Money is a powerful incentive, and when used properly, it is a powerful driver for improvement. Strategic use of financial incentive is part of policies. To meet the future challenges, leaders will have to develop the right kind of incentives. The focus will have to be on efficiency, on long-term continuity of production potential as well as on short-term performance. The financial incentives can be subsidies. Although the debates tend to make believe subsidies are all bad, there are good and useful subsidies. Another area of incentives to think about is the type of bonuses paid to executives. Just imagine what would happen if, instead of just profit, the carbon footprint per $1000 of sales was factored in the bonus? Gas emissions would be high on the priority of management teams.

If the way executives are paid matters, the type of financial structure of businesses could influence the way they operate, too. Now, it may sound surprising, but in the future, expect the question whether food companies should be listed on the stock exchange to arise. Short-term focus on the share price can be quite distracting from the long-term necessities. If we find that elected officials are short-term-oriented because elections take place every four or five years, how short-term quarterly financial results to the stock markets influence CEOs? The pressure by investors on companies’ Executive Boards to deliver value is high. They expect some results within a relatively short period, while what happens to the companies, their employees and long-term effect on the environment after they took their profits is irrelevant to them. This brings the question of the functioning of financial markets as a whole. What derivatives are acceptable? Who should be allowed to have access to which ones? What quantity could they be allowed to buy and sell? Many questions will arise more and more loudly every time food prices will jump up again the future, and as social unrest may result from it.

To prepare the future, it is important to prepare the generations of the future. Education will play a critical role in the success of societies. Only by helping future generations to have access to knowledge, to develop skills and to train to fill in the jobs of the future, will countries develop a strong middle class. Thanks to education, people can get better paying jobs. This allows them to buy adequate quantities of food for themselves and their families. Education is an investment to fight poverty and hunger. In the agricultural sector, it will be important to attract more young people to work in the food and agricultural sector. In many countries, farmers are getting old and replacement is scarce.

These are just a few of the issues that the current and future leadership will have to solve, if we want the feed and preserve the world. There will be many discussions about which systems are the best suited to ensure prosperity and stability. The respective roles of governments, businesses, non-profits and of the people will certainly be reviewed with scrutiny.

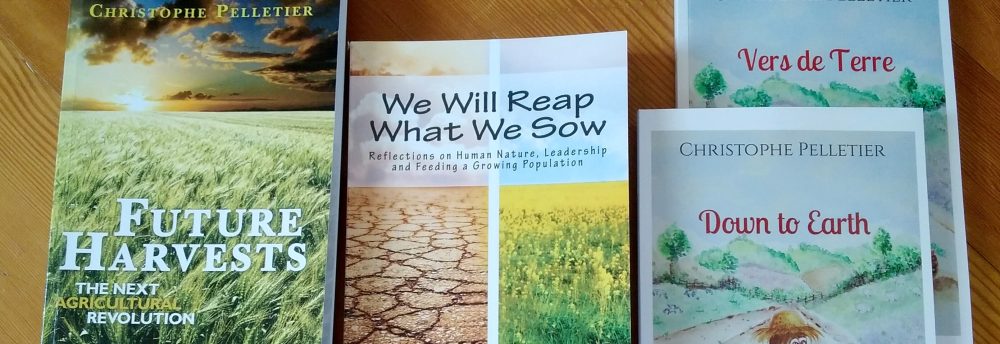

During the writing of Future Harvests, it became obvious to me how crucial the role of leadership is for our chances of success. In the course of a number of assignments with my company, this observation has grown even stronger.

For these reasons, I have decided to start writing another book focused on the role of leadership to develop long-term development of food production and food supply. It will be a reflection about the tough calls that leaders need to make. The final objective is to ensure viable food production systems and proper infrastructure, while ensuring the continuity of food supply in the long-term, through a successful interaction between all stakeholders.

Tentatively, the publication date is fixed for the summer or the fall of 2012.

Copyright 2011 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

Of course, if you follow social media, you know that, immediately, the partisans, mostly in the Midwest, spread the good news as fast and as much as they could. To them, this number of 155 is the best proof that large-scale industrial technology and mechanization driven agriculture is the best there is, and US farmers are the best in the world! So that the world knows it this time!

Of course, if you follow social media, you know that, immediately, the partisans, mostly in the Midwest, spread the good news as fast and as much as they could. To them, this number of 155 is the best proof that large-scale industrial technology and mechanization driven agriculture is the best there is, and US farmers are the best in the world! So that the world knows it this time!

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity.

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity.