The road to ensure food security for all is still long. Although humans are very creative to solve and overcome their problems, when it comes to food production, they still lack control on many parameters. Since the beginning of agriculture, farmers have watched towards the sky to see what the weather would bring them. Rituals to call for friendly climatic conditions and soil fertility have been common in all cultures. Droughts, floods, never-ending rainfall, frost and other climatic events have happened on an ongoing basis and, climate change or not, they still will happen in the future. If natural events are out of our control, we can influence another parameter, although mankind’s history has shown that it is a difficult one to tackle: the human factor.

Here follows in condensed form my top ten human limitations to succeed in feeding nine billion people by 2050:

#10: Fear

Although fear is a defence mechanism, it will not protect humanity against food shortages. There are many fears that play a role in our understanding (or lack of it) of food production. The problem is not so much fear itself, but the inability to overcome it and to start bringing effective solutions to the problems. The other risk that fear brings is its ability to spread and to evolve into panic.

There are many challenges ahead, but we need to keep our heads cool, and address the issues practically and rationally, at least as much as we can. Inaction, which is a symptom of fear, will not be helpful. To feed nine billion we cannot be passive.

#9: Greed

Greed is fear’s twin sibling. It is a strong driver that makes people take risks for the sake of material reward. As such, a little bit of greed is good, as it stimulates action and entrepreneurship. It stimulates the need for action that I just mentioned. Speculation, the purest form of greed, will have to be brought under control. Its consequences in terms of social unrest and on the stability of societies are too serious. The risk with greed is that all the focus is on the short-term financial reward. It is also essential to ensure the continuity of food production for the long term, and we should not engage in solutions that can undermine future food security. A little bit of fear will help bring some balance.

#8: Not addressing the right issues

This, together with the slow disappearance of common sense, is a growing tendency. Too often, the focus is on eliminating the symptom rather than the cause of the problem. This usually results in creating a new set of unnecessary problems. By eliminating the cause of a problem, the solution does not create any new problem. We just have to deal with other problems and their causes. In the case of food security, an example of mistaking the cause and the symptom is hunger. The cause is poverty, not the lack of food. The food is there, but the poor cannot afford it. In our world of information overflow where the media are more interested in the sensational and the “sexy”, true and thorough analysis has gradually become less interesting to the public. Although analysis may be boring indeed, it is an absolute necessity if we really want to solve problems.

#7: Lack of education/training

Here is a topic that rarely makes the headlines in the media. Farmers, and candidates farmers, need to have access to proper education and training. In order to improve and produce both more and better, they need to have the knowledge and have the possibility to update this knowledge. This may seem obvious in rich countries where education and training are well organized, but in many developing nations, usually plagued with food insecurity, this is not the case. Too often, even the most basic knowledge is missing. For these populations to succeed and to contribute in increased food security, it is necessary to have education high on the list of priorities.

#6: Lack of farmers

This topic does not get much publicity, although it is of the highest importance. In many countries, the average age of farmers is above average and there seems to be little interest from the youth to take over. We need farmers if we want food. To have farmers, we need to make the profession attractive and economically viable. Two weeks ago, the US Secretary of Agriculture announced measures to make it easier to start up a farm. He mentioned that his country needs to find 100,000 new farmers. In Japan, they are developing robots to do the farmers’ work as there is too little interest from the youth for agriculture, and they face a serious risk of not having enough farmers. In the EU, there are more than 4.5 million farmers older than 65, while there are fewer than 1 million farmers younger than 30. This is how serious the situation is becoming.

#5: Lack of compassion/Indifference

In our increasingly individualistic and materialistic societies, the focus has shifted towards the short term, and even to instant gratification. Our attention span has shrunk dramatically, and unless other people’s problems affect us, we tend to forget about it. When it comes to food security for nine billion people, this will not work. There are many possibilities to produce enough food, as I have shown in previous articles, but to achieve this goal, we still have a lot of work to do. Mostly, we have to change a number of bad habits.

Throwing large amounts of food in the garbage is one of those bad habits. By changing this, we can save amazing quantities of food. First, we must lose the I-do-not-care attitude.

Large quantities of food are lost before reaching markets in developing countries. All it takes to solve the problem is to make the funds available. Compared with the stimulus packages and bank bailouts, the amount is ridiculously low. There too, the not-my-problem attitude is improper.

Another example is Africa. With the size of Australia of unexploited arable land, and low yields because of lack of proper seed and proper support, the potential for food production is huge. We need to help Africa succeed. The attitude of the West towards Africa, and Africans, needs to change.

Humans are social animals. This behaviour is an evolutionary advantage aimed at ensuring the survival of the species. Hard-nosed individualism and indifference go in the opposite direction. They work only in period of abundance. By showing some compassion and helping others succeed, the fortunate ones actually increase their own odds of survival. In our globally interconnected world, any negative food security event affects us all, eventually. We feel a pinch while we are “only” seven billion. This says how painful it would be by being nine billion.

#4: Interest groups

A better name should be self-interest groups. There is not a day that goes by without showing us the total lack of interest they have for those who are not affiliated to them. For as much as it is essential that all opinions and philosophies can express themselves, it is just as essential that they also have empathy and respect for those who think differently. Interest groups do not appear to do that. They express the behaviours that I indicate under #10, #9, #8 and #5. Their objective is to influence policies by bypassing the people who elected the representatives who depend on these groups for their political funding. Would that sound accidentally reminiscent of corruption and banana republic?

#3: Lack of long-term commitment to the vision/plan

There are many plans for food security out there. About every government has one. Industry groups come out with their vision as well. So do environmental groups. The problem in many cases is not the lack of objectives; it is the failure of execution.

To achieve food security, proper execution is paramount. It requires much more than a vision and a plan on paper. It requires a clear allocation of responsibilities and a schedule for the delivery of the objectives.

Often, what undermines the execution of a plan is the lack of a sense of ownership of the mission. All the actors of food security need to be involved as early s possible in the process. This makes them participate in the set up of the plan and this increases their level of commitment. There is nothing worse than a plan developed by a limited group that tries to push it on those who actually must make it happen. When people are not involved and committed, they feel no ownership of the plan. They simply will not participate.

#2: Ego

There is nothing like some good old-fashioned ego to thwart the general interest. Unfortunately, ego is a rather common component in higher circles of government, business and organizations. Some of the symptoms include the inability to say “I don’t Know”, the inability to admit being wrong, the tendency to wage turf wars, and the unawareness of the win-win concept. Acknowledging one’s ignorance is the first step to learning, therefore improving. Believing to be always right is simply delusional and shows a lack of sense of reality. Turf wars may end up with a winner, but usually it is a Pyrrhic victory. Thinking that one can win only if the others lose is just an illustration of point #5. When it comes to food security for nine billion, a short-term victory at someone else’s expenses will soon be a defeat for all.

#1: Poor leadership

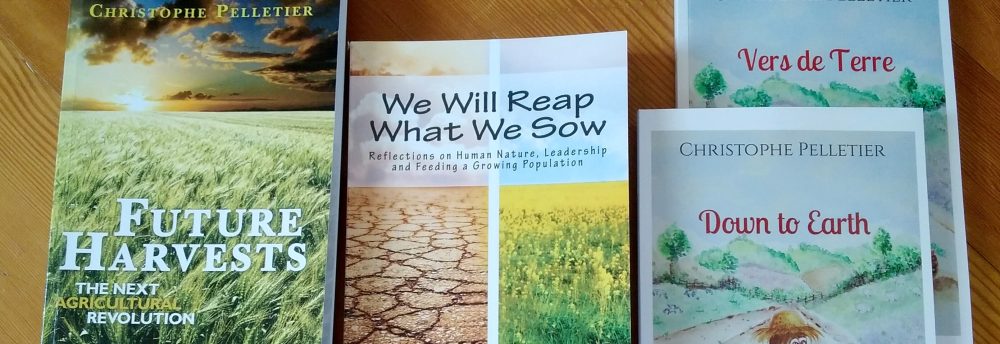

Leadership is paramount in any human endeavour and feeding nine billion is quite the objective. While I was writing Future Harvests, I constantly came across the importance of leadership. I have no worries in our technical abilities.

All the success stories that I could learn from had all in common having a strong leader with a clear vision of what needs to be done. The leader also had the ability to gather all the energies behind him and get a consensus on the objectives and the path to follow.

Similarly, all the failures stories also had leadership in common. Usually, it shows a despotic leader who acts more out of self-interest than for the general interest, who does not accept being wrong and change course before things go haywire.

In order to succeed and meet food demand by 2050, we will need leaders, at all levels of society, who have the following qualities. They will overcome fear, keep greed under control, address the right issues, will foster education, will encourage farmers’ vocations, will be compassionate, will work for the general interest, will involve and commit all to succeed, and will not put their egos first.

Copyright 2011 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity.

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity. The job description is, interestingly enough, rather reminiscent of food production and genetics. In order to express the full potential of its genes, an organism needs the proper environment. This is exactly the role of the future leaders. They must create the conditions that will allow farmers to produce efficiently, yet sustainably.

The job description is, interestingly enough, rather reminiscent of food production and genetics. In order to express the full potential of its genes, an organism needs the proper environment. This is exactly the role of the future leaders. They must create the conditions that will allow farmers to produce efficiently, yet sustainably. Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong.

Then, is one planet enough or not? Simple math should help finding the answer. If we need two Earths to feed nine billion, one planet would only feed 4.5 billion people. Currently, the world population is around seven billion, out of which one billion is hungry. Conclusion is that we currently can feed about six billion people. We are not doing that bad. Is it possible to find ways of feeding three more billion on this Earth? From the simple math above, it is clear that those who claim that we need three Earths or more are wrong. To attract new people to the food sector, it is also quite important to tell what kind of jobs this sector has to offer. These jobs need to be not only interesting, but they also must offer the candidates the prospect of competitive income, long-term opportunities, and a perceived positive social status. Many students have no idea about the amazing diversity of jobs that agriculture (including aquaculture) and food production have to offer. This is what both the sector and the schools must communicate. Just to name a few and in no particular order, here are some of the possibilities: farming, processing, logistics, planning, sales, marketing, trade, operations, procurement, quality, customer service, IT, banking and finance, nutrition (both animal and human), agronomy, animal husbandry, genetics, microbiology, biochemistry, soil science, ecology, climatology, equipment, machinery, fertilizers, irrigation, consumer products, retail, research, education, plant protection, communication and PR, legal, management, knowledge transfer, innovation, politics, services, etc… Now, you may breathe again!

To attract new people to the food sector, it is also quite important to tell what kind of jobs this sector has to offer. These jobs need to be not only interesting, but they also must offer the candidates the prospect of competitive income, long-term opportunities, and a perceived positive social status. Many students have no idea about the amazing diversity of jobs that agriculture (including aquaculture) and food production have to offer. This is what both the sector and the schools must communicate. Just to name a few and in no particular order, here are some of the possibilities: farming, processing, logistics, planning, sales, marketing, trade, operations, procurement, quality, customer service, IT, banking and finance, nutrition (both animal and human), agronomy, animal husbandry, genetics, microbiology, biochemistry, soil science, ecology, climatology, equipment, machinery, fertilizers, irrigation, consumer products, retail, research, education, plant protection, communication and PR, legal, management, knowledge transfer, innovation, politics, services, etc… Now, you may breathe again! This time, there is one major difference. With 9 billion people in sight by 2050, the consequences of our actions will have much more impact, negative as well as positive, depending on where we live. In 1950, there were “only” 2.5 billion people on Earth. Compared with today, one could argue that there was some margin for error by then. This margin for error is now gone. Therefore, it is necessary to think ahead and consider all the things that might go wrong. We must anticipate before we have to react.

This time, there is one major difference. With 9 billion people in sight by 2050, the consequences of our actions will have much more impact, negative as well as positive, depending on where we live. In 1950, there were “only” 2.5 billion people on Earth. Compared with today, one could argue that there was some margin for error by then. This margin for error is now gone. Therefore, it is necessary to think ahead and consider all the things that might go wrong. We must anticipate before we have to react.