Since the drought in the US of this past summer and the strong price increase of agricultural commodities, agriculture has become a favorite topic in the media. As such, this would be really good if it were not for the (potential) disaster voyeurism. There is nothing like a flavor of end of the world in the works to get the attention of the readers. After all, this is good to fill advertising space and to promote a book.

Since I started to look at the future of food and farming, I have seen an evolution on how people look at the future of agriculture. When I started, I could hear statements about the need to have two (even three and four) Earths to meet demand. Interestingly, none of those who stated this impossibility neglected to pay attention to food losses, and they were only focusing on more production. When could passing a mop under an open tap be a sensible approach? If we really come to need more than one planet, then there is only one outcome. Since that second Earth does not exist, the surplus of people would have to die so that the world can meet the demand of the survivors. I agree that it is not a cheerful thought. However, Mao Tze Tung once considered that it could be acceptable that half of his people, the poor, would die of famine to allow the other half that could afford food to be able to meet its needs. Such a morbid thought is actually more common that one would admit, and in this world of political correctness, it is repressed voluntarily. That does not stop the fear mongers, though. They just not choose to sacrifice a group to save another one. They tell us that we are all going to face our demise. That is politically correct, I suppose. Personally, I do not consider that announcing disasters is constructive. Fear is a poor adviser, and it is certainly not the proper way to communicate about problems.

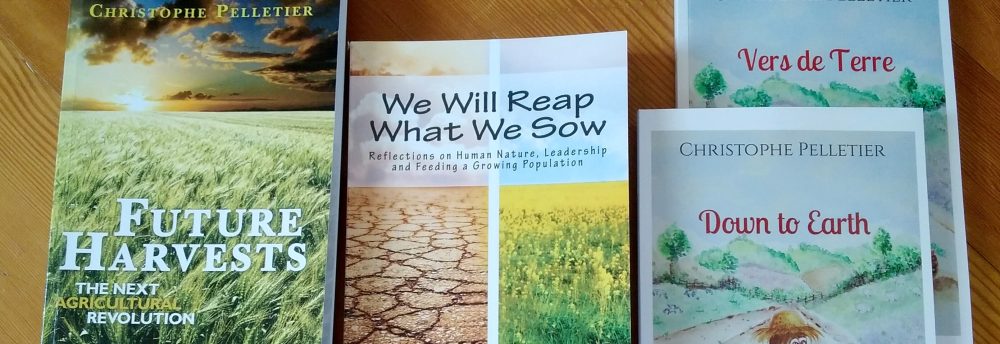

There is no shortage of doomsday thinkers out there. In We Will Reap What We Sow, I address the many challenges that the doomsday thinkers bring up. Instead of taking an apocalyptic approach like they do, I chose to initiate a positive reflection about alternatives and solutions. Scaring people is too easy, especially when they are not experts in the field of agriculture. I am not a fan of the one-eyed being king in the land of the blind. I have 20/20 vision and I want to help others to also see with both eyes. In my book, I make clear that we will live with the consequences of our actions (hence the title), but I give many reasons for hope. It is more productive then despair.

In the realm of doom and gloom, I must admit that the Post Carbon Institute wins the prize. Among the other prophets of doom, Lester Brown currently fills the stage, especially since he is promoting his latest book. I had the chance to hear him speak some 14 years ago at an aquaculture conference. I must say that he is an excellent speaker and quite a charming man. Actually, he inspired me to venture into foresight and futurism. I really believe that his talents should be used to create positive momentum instead of sowing depressive thoughts in the population. Before the summer (before the US drought that is), he had stated in an interview that “the world is only one bad harvest away from a food crisis”. I have never subscribed to that point of view. The issue of feeding the world is much more complex than that. Well, we just have had a bad harvest and there is no more food crisis than last year. Prices of agricultural commodities have gone through the roof. Yet, there have not been any riots like in 2008. It is almost a wonder considering how much fear mongering has taken place in the mainstream media. They all came with scarier scenarios the one than the other. And thanks to social media, the news spreads even faster and further. In particular, Twitter is an amazing place to be in. Anything and everything gets tweeted, retweeted many times over without the slightest critical thinking. Their symbol should not be a bird. It should be a sheep. The top of uncritical maniacal tweeting was about the writer from Australia who spoke at a conference telling the audience that agriculture needs to produce 600 quadrillion calories a day. That was all over twitter. Wow, do you fancy that, 600 quadrillion? Yes, I have to admit it is a big number. I found is so big that I had to count on my fingers. Considering that the average human being needs about 2,000 calories a day (the FAO says 1,800, but let’s keep the calculation simple!), 600 quadrillion calories corresponds to the needs of 300 trillion people. That is about more than 40,000 (yes, forty thousand) times more than the current world population. With math like this, it should be no surprise that his book is titled the Coming Famine. Regardless of the title, I would agree that one Earth could not feed any number of people remotely close to 300 trillion, but we are not there yet. When I saw that number, I could not resist tweeting about the math, and the sheeple out there realized that the numbers did not add up.

That has not been the end of my tweeting against the fueling of fears about food and agriculture. Another tweet that caught my attention came from Graziano da Silva, Director General of the FAO (actually his staff) stating about food prices “This is not a crisis yet. We need to avoid “panic buying””, to which I replied that a good way to do this could be to stop talking about food crisis so often. What can be more of a boon to speculators in commodities than Twitter and its instant worldwide spreading of any rumor, information or myth that indeed can create panic? There is no better way to make food prices increase than by repeating exponentially that there might be food shortages, even though it is not the case. Interestingly enough, since then, the panic button seems to have been turned off at the FAO.

Fear mongering and doomsday thinking, although morbidly attractive, will not help build a solid future. Predicting terrible disasters without giving clear clues of how to prevent and overcome them is rather useless. Actually, it is counterproductive. Those who do not know the facts or are not in a position of doing something about the problem are going to feel demotivated and there is a chance that they will not try to care anymore. Those who actually contribute to solutions will not pay much attention, as it sounds like the kid who cried wolf to them, and might miss important information in the process. There are challenges ahead. Some of them are quite serious and difficult to overcome, but not impossible. I know that and I know them. And so do many others. However, the fact that the task ahead is challenging is no reason to undermine anyone’s morale. The amount of knowledge and of tools at our disposal is quite amazing, and we probably have more than we need to fix things. What must change is our attitude. Rambling and whining about problems have never made any disappear. It is necessary to create positive momentum among the population(s), to show them that success is possible. To achieve this, it is important to avoid the opposite of fear mongering, which is blissful optimism. It is possible to feed the world, even when it reaches 9 billion people. It can be done with one Earth. A couple of years ago, I was one of the few who claimed that it could be done. By then I felt a bit lonely, as the main thinking sounded like it could not be achieved. Maybe my blog, books and presentations have contributed to change that. Those who have read me or listened to me seem to think that my positive and practical look on the issue have contributed to changing their mindset. The thought is nice, but it is not what counts. What really matters is that gradually, more people start to see beyond the myths and the catch phrases. Not everyone does. This summer, I heard about the “Great Global Food Crisis”. So far, I had heard only about the Global Food Crisis. Apparently, fear had increased by a notch or two. Such expressions are non-sense. If the food crisis were to be global, there would be a food crisis everywhere around the globe. That is pretty much the definition. I do not see any food crisis in many countries. Actually, a study showed that the number of overweight people was on the rise in more and more countries. What is true is that there are local food crises. Unfortunately, for the populations that suffer from it, they are not caused by global food shortages as some like to make believe, but because of armed conflict and /or by poverty and lack of infrastructure. The number of undernourished people is actually decreasing as the FAO showed in their latest State of Food Insecurity 2012. To me, everything points at progress in the fight against hunger, even though negative climatic events affect agricultural production. But just for fun, let’s get back to the Great Crisis. If the food crisis were to be global, can it get any bigger than that? What does the adjective Great add? It adds nothing except the desire to scare. Let’s face it! Some people jobs depend on cultivating the idea that something goes wrong. It is their only purpose. Personally, I prefer those who roll up the sleeves and conceive, develop and execute solutions. These are the ones who make our future world a better place. It is too bad that they do not get as much attention from the media as the fear mongers. Of course, things that go well are not as sensational as disasters, but they are more valuable. They are the success stories that need to be told, so that others can learn from them. They are the success stories that must be told so that we all eventually can realize that building a solid future is possible. It is not easy as spreading fear, but it is much more productive and useful for present and future generations!

Copyright 2012 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

I often tell that the difference between the effects of the financial, the social and the environmental parts of the economy manifest at different speed. Anyone can follow share prices live on the stock market, anyone can follow his/her bank account on a second-by-second if desiring to do so. Social consequences can take months or longer to manifest, and environmental effects can take decades to manifest. The financial crisis has been the result of postponing actions to ensure that the money world could be sustainable. It is still far from being there and the financial crisis is not over, but at least there was the possibility to print money and to emit debt. That entertains the illusion. When it comes to environmental sustainability, our leaders are also postponing actions to ensure that our physical world be sustainable. The main difference is that there is no printing of Nature possible. Printing of wheat, rice, beans or other essential food items is not an option. If we lose the ability to produce enough, there will be fights for food. That is inevitable.

I often tell that the difference between the effects of the financial, the social and the environmental parts of the economy manifest at different speed. Anyone can follow share prices live on the stock market, anyone can follow his/her bank account on a second-by-second if desiring to do so. Social consequences can take months or longer to manifest, and environmental effects can take decades to manifest. The financial crisis has been the result of postponing actions to ensure that the money world could be sustainable. It is still far from being there and the financial crisis is not over, but at least there was the possibility to print money and to emit debt. That entertains the illusion. When it comes to environmental sustainability, our leaders are also postponing actions to ensure that our physical world be sustainable. The main difference is that there is no printing of Nature possible. Printing of wheat, rice, beans or other essential food items is not an option. If we lose the ability to produce enough, there will be fights for food. That is inevitable.

Every activity that pollutes without cleaning the contaminants is a negative externality. Everything that damages physically the environment and undermines the sustainability of food production is a negative externality. Every activity that depletes essential resources for the production of food is a negative externality. In this highly industrialized world, the consequences of economic and human activities, slowly add up. Nature’s resilience makes it possible for damage to remain unnoticed for quite some time. However, the ability of Nature to repair the damage shrinks, as the damage is continuous and exceeds Nature’s ability to cope with the problem. As the population increases, the level of human and economic activities intensifies further. There will come a time when Nature simply cannot handle the damage and repair it in a timely manner anymore. The buffer will be full. When this happens, the effect of negative externalities will manifest immediately, and it will include the cumulated damage over decades as well. It will feel like not paying the bills for a long time and then having all belongings repossessed. Humanity will feel stripped and highly vulnerable. The advisory services company KPMG published a report in 2012 stating that if companies had to pay for the environmental cost of their production, it would cost them an average 41% of their corporate earnings. These costs are currently not included in the pricing. That is how high negative externalities can be. Looking at it from the other way, companies would still deliver 59% of their current earnings. Repairing the damage and still generate profits shows that sustainability is financially achievable. On average, the profits would only be lower, but the impact would vary substantially between companies. Businesses that create high negative externalities will show much bigger drops in profits, than business that do the right thing. The only ones who would have to get over some disappointment would be Wall Street investors and all those who chase capital gains on company shares. The world could live with that. Investors should put their money only in companies that actually have a future.

Every activity that pollutes without cleaning the contaminants is a negative externality. Everything that damages physically the environment and undermines the sustainability of food production is a negative externality. Every activity that depletes essential resources for the production of food is a negative externality. In this highly industrialized world, the consequences of economic and human activities, slowly add up. Nature’s resilience makes it possible for damage to remain unnoticed for quite some time. However, the ability of Nature to repair the damage shrinks, as the damage is continuous and exceeds Nature’s ability to cope with the problem. As the population increases, the level of human and economic activities intensifies further. There will come a time when Nature simply cannot handle the damage and repair it in a timely manner anymore. The buffer will be full. When this happens, the effect of negative externalities will manifest immediately, and it will include the cumulated damage over decades as well. It will feel like not paying the bills for a long time and then having all belongings repossessed. Humanity will feel stripped and highly vulnerable. The advisory services company KPMG published a report in 2012 stating that if companies had to pay for the environmental cost of their production, it would cost them an average 41% of their corporate earnings. These costs are currently not included in the pricing. That is how high negative externalities can be. Looking at it from the other way, companies would still deliver 59% of their current earnings. Repairing the damage and still generate profits shows that sustainability is financially achievable. On average, the profits would only be lower, but the impact would vary substantially between companies. Businesses that create high negative externalities will show much bigger drops in profits, than business that do the right thing. The only ones who would have to get over some disappointment would be Wall Street investors and all those who chase capital gains on company shares. The world could live with that. Investors should put their money only in companies that actually have a future.