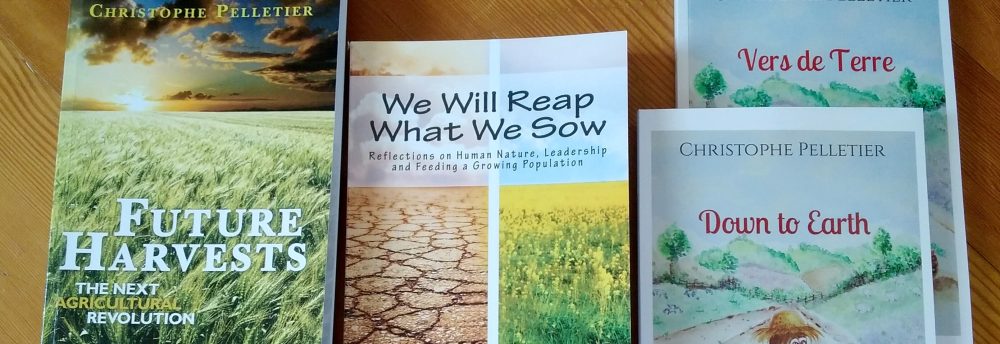

The complete story about this topic and how it will influence the future markets can be found in my book We Will Reap What We Sow.

The size of the world population is among the most significant changes for the future. There are many challenges, as the media tell us on a daily basis, but there are opportunities. The first and the main of these opportunities is the population increase itself. In the coming four decades, there will be two billion more people to feed. Never before, has humanity seen such a demand increase. This means that farmers and food suppliers do not have to worry about a lack of market opportunities. Not only the number of people will increase, but the consumption pattern will change, too.

Until recently, most of the consumption took place in industrial countries, mostly the USA, the EU and Japan. For the coming decades, food consumption in these areas will not increase. There are simple reasons for this. One is the demographic stagnation of industrialized regions. Another reason is that people of these regions already eat too much. They have no room for more consumption. At best, they can replace one food by another. Before the economic crisis of 2008, the average daily intake of calories per American was on average of 3,800. This amount is about 50% more calories higher than a normal human being needs on a daily basis. Nobody should be surprised that in such conditions a third of Americans are obese.

In emerging countries, the economic growth results in the rise of a new middle class. A change of diet is the first change that takes place when the standard of living increases. People switch from staple foods such as rice or wheat to higher quantities of animal protein and more fruit and vegetables. The OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) looked at the future evolution of the respective shares of consumption by the middle class, between different regions of the world. Their study was for consumption goods at large. The graph is simply amazing.

Click on the picture see the enlarged versionThe relative consumption of Western countries will shrink dramatically. While the USA represented about 5% of the world population in 2000 and consumed about 25% of the world resources, they will represent only about 4% of the population and consume about 4% as well. A similar evolution will take place in the EU and in Japan. China and India show the opposite trend. With a share of the total world consumption close to negligible percentages a few years ago, their economic development and the size of their middle classes will transform markets dramatically. Estimates are that the middle class from China and India combined will represent about 45% of the world middle class by 2030! Market demand and therefore world prices will be dictated by the demand from these two countries and not by Western countries anymore.

While the graph covers all consumption items, the situation for food alone might show some differences, but the trend would show a similar pattern. The demand for food in emerging countries will grow strongly. This will not affect only the consumption volumes but also the type of food. The change of the type of food that consumers of the middle class of emerging countries will demand will go beyond switching from a starch-based diet to an animal-protein-rich diet. The type of animal protein that they will eat will change, too. A couple of decades ago, China would import many of the low quality animal products that Western consumers did not want to eat. China used to import products such as chicken feet, chicken wingtips, sow uteri or fish heads. The new middle class is no longer much hungry about those products. They want the prime cuts, too. Instead of being complementary, emerging markets and developed countries will be in competition with each other for the better animal products. This will have profound consequences for the future. It will make the sale of the low-quality products more difficult and affect negatively the profitability of meat producers. At the same time, it will make the demand for prime products literally explode, pushing prices up. Western consumers and Western markets used to set the prices. In the future, Western consumers will have to buy food based on the price set in Asia. Their alternative will be to not have access to these prime products anymore and have a choice between changing their diets or eat less animal products.

This change will make producers and buyers look at business opportunities in a completely different manner than they currently do. All emerging countries show the same trend. Brazil now sees domestic demand for chicken meat increase faster than export markets. Brazilians eat more meat because they become wealthier. Chilean salmon farmers see growing possibilities in the Brazilian market. While their traditional market for Atlantic salmon was the US market, this may change. Since air transport from Chile to the USA is quite expensive, at least more expensive than transport to Brazil, the flow of trade will change from the past. Norwegian salmon might become a better alternative, but the Chinese are now buying increasing quantities. American buyers must prepare themselves to pay much more than in the past to get salmon products.

It becomes clear that the challenge of feeding the world depends for a large part on future consumption of animal protein.

To understand the effect of the increase of consumption of meat in China, a few numbers are helpful. When 1.5 billion people eat on average 1 kg more of chicken meat, world production needs to increase by about 750 million chickens. That represents about 2% of the world production. Similarly, when the Chinese consume on average 1 kg of pork more, the world must produce 15 million pigs more. That number represents 1.5% of the world pig production. The meat consumption in China has already passed the milestone of 50 kg per capita per year, and projections indicate that it would reach 8o kg per capita per year in 2030. Clearly, consumption increase will be much more than just 1 kg. An increase of 10 kg of chicken meat per capita per year in China means that chicken production would have to increase by 20% to meet the new demand! This represents almost the US chicken production volume, and more than Brazilian production. In the case of pork, an increase of consumption of 10 kg per capita means that world pig production would have to increase by 15%. That is 5 times the current pig production of Iowa. That is 60% of the EU production. For beef, the world production would have to increase by 24% to meet an increase of 10 kg per capita per year! This number also represents about 25% more than the current total beef US production.

The Indian population, although still largely vegetarian, is also changing its eating habits. Meat production is increasing there, but not in such dramatic proportions as in China. Nonetheless, with a population of 1.2 billion people, any incremental meat consumption will have consequences.

Different animal productions have different levels of feed efficiency. It takes about 1.8 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of chicken meat. It takes about 3 kg of feed to produce 1 kg of pig meat. For beef, depending on how much grass the animals are fed, the amount of grain used to produce 1 kg of beef varies. With a population of 1.5 billion, an increase of meat consumption of 30 kg would result in the need to produce 3 times 30 times 1.5 billion. The need for feed, excluding grass, would be between 100 and 150 million tons of grains.

Human consumption of grains increase rather limited. Considering that in 2011, animal feed uses about a third of all grains produced, more production of animal protein will put much more pressure on the markets of agricultural commodity. Producing enough to meet the desires of a more affluent world population is actually about allowing the luxury of more meat than people really need. There is no doubt that the “meat question” will become more and more vivid in the future.

My next book, We Will Reap What We Sow, will get in depth about this topic and many others, and discuss the pros and cons of different future scenarios. Stay tuned!

Copyright 2011 – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity.

If there is a sensitive topic about diet, this has to be meat. Opinions vary from one extreme to another. Some advocate a total rejection of meat and meat production, which would be the cause for most of hunger and environmental damage, even climate change. Others shout something that sounds like “don’t touch my meat!”, calling on some right that they might have to do as they please, or so they like to think. The truth, like most things in life, is in the middle. Meat is fine when consumed with moderation. Eating more than 100 kg per year will not make you healthier than if you eat only 30 kg. It might provide more pleasure for some, though. I should know. My father was a butcher and I grew up with lots of meat available. During the growth years as a teenager, I could gulp a pound of ground meat just like that. I eat a lot less nowadays. I choose quality before quantity. They are perceived as independent, although this is not necessarily the case, and this tends to give them a higher moral status, especially compared with the for-profit sector. As I had written in a previous article, nobody has the monopoly of morals, but non-profits have a PR advantage in this area. A part of their strength comes from the loss of trust in government, science, industry and politics by the general public. In the food and agriculture sector, the influence of non-profit organizations is growing, and it challenges the way food is produced.

They are perceived as independent, although this is not necessarily the case, and this tends to give them a higher moral status, especially compared with the for-profit sector. As I had written in a previous article, nobody has the monopoly of morals, but non-profits have a PR advantage in this area. A part of their strength comes from the loss of trust in government, science, industry and politics by the general public. In the food and agriculture sector, the influence of non-profit organizations is growing, and it challenges the way food is produced. This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water.

This movement is rather popular here in Vancouver, British Columbia. The laid-back residents who support the local food paradigm certainly love their cup of coffee and their beer. Wait a minute! There is no coffee plantation anywhere around here. There is not much barley produced around Vancouver, either. Life should be possible without these two beverages, should not it? The disappearance of coffee –and tea- from our households will make the lack of sugar beets less painful. This is good because sugar beets are not produced in the region. At least, there is no shortage of water. For most customers, white eggs are perceived as being from intensive cage production, while brown eggs are perceived as being more “natural”. Everyone with knowledge of the industry knows that the color of the shell has nothing to do with the nutritional quality of the egg. The belief that the egg color indicates a difference persists, though.

For most customers, white eggs are perceived as being from intensive cage production, while brown eggs are perceived as being more “natural”. Everyone with knowledge of the industry knows that the color of the shell has nothing to do with the nutritional quality of the egg. The belief that the egg color indicates a difference persists, though. Of course, it would be interesting to imagine what people would eat if they were rational, and what impact on our food production this would have. A rational diet would follow proper nutritional recommendation, and to this extent would follow the same principles as those used in animal nutrition. However, this would not have to be as boring a diet as what animals are fed. A rational diet does not need to be a ration. After, the human genius that is cooking would help prepare delicious rational meals. It would be like having the best of both worlds. The emotional, social and hedonistic functions of food would remain. The key would be about balance and moderation. If people were eating rationally, there would not be any diet-related illnesses. There would not be obesity. There also would be a lot less food waste. This would improve the level of sustainability of agriculture.

Of course, it would be interesting to imagine what people would eat if they were rational, and what impact on our food production this would have. A rational diet would follow proper nutritional recommendation, and to this extent would follow the same principles as those used in animal nutrition. However, this would not have to be as boring a diet as what animals are fed. A rational diet does not need to be a ration. After, the human genius that is cooking would help prepare delicious rational meals. It would be like having the best of both worlds. The emotional, social and hedonistic functions of food would remain. The key would be about balance and moderation. If people were eating rationally, there would not be any diet-related illnesses. There would not be obesity. There also would be a lot less food waste. This would improve the level of sustainability of agriculture. fact, they will hardly listen. Therefore, words will have little impact, unless they go along with actions that confirm that the message is true. If the food industry does not want to change and hopes that communication will be enough to change the public’s mind, nothing will change. When you want someone to prove to you that he/she is reliable, you want to see tangible proof that something is changing in your favor. The most powerful communication tool that really works for regaining trust is the non-verbal communication. The distrusted one must sweat to win trust back. This does not take away that verbal communication must continue. It will keep the relationship alive, but it will not be the critical part for turning around the situation.

fact, they will hardly listen. Therefore, words will have little impact, unless they go along with actions that confirm that the message is true. If the food industry does not want to change and hopes that communication will be enough to change the public’s mind, nothing will change. When you want someone to prove to you that he/she is reliable, you want to see tangible proof that something is changing in your favor. The most powerful communication tool that really works for regaining trust is the non-verbal communication. The distrusted one must sweat to win trust back. This does not take away that verbal communication must continue. It will keep the relationship alive, but it will not be the critical part for turning around the situation.