Listen here to a Chrome AI-generated podcast type playback of the author’s article

In my previous blog article, I was mentioning the growing population. This topic has been keeping many people busy for a long time. By the end of the 18th century-early 19th century, Thomas Malthus predicted that the human population would exceed the amount of food it can produce to feed itself. By then, the world population was less than one billion people. His views, so far, have proven wrong, although there indeed could be a maximum number of people that is viable. What is this number? Nobody knows for sure but there are many opinions out there.

A quick exercise I did recently as part of a presentation about the future of food production and consumption was to make people think about how we use agricultural land. My purpose was to take distance from all the usual narratives and provoke some thoughts in a playful manner. It is not so much about some hard numbers, as it is about thinking differently and looking at the world and the future from a different angle. I brought up a few topics.

Technical performance

There is a debate about extensive and intensive agriculture. In my opinion, this is the wrong debate in the sense that these are just two qualitative adjectives. They are not quantitative, so everyone can use them as they please. They do not tell what the acceptable limit of intensification is.

I prefer to speak of efficiency. Many people, even in academia, seem to confuse intensification with efficiency. That is a serious mistake. The key is to find the particular point of the maximum intensification that does not compromise sustainability. I discuss that in one of my YouTube videos, which I also have a shorter version just focusing on what I think sustainable intensification means.

To make a long story short, and from a perspective of sustainable intensification, better yields mean less land necessary. Same thing with animal farming: higher productive animals need less feed per kg of final animal product relatively because the energy needs for maintenance are lower, therefore less land. And from a perspective of the so popular cow burps as they are called nowadays, let’s take a simple example. Let’s compare one cow producing 9,000 liters of milk vs. three cows producing 3,000 liters each. It is rather obvious that the one cow will burp less than three cows combined, therefore less methane, therefore better from an environmental point of view.

The main lesson from this is simple: genetics play a critical role for sustainability.

Biofuels

An interesting study by the Institut für Energie und Umweltforschung (Institute for Energy and Environmental Research) from Heidelberg, Germany has been published in 2023. In their conclusion, the authors determined that the farm area used in the European Union for crops destined to the production of biofuels (ethanol and biodiesel) represented an area the size of the entire island of Ireland and could feed a population of about 120 million people. This is interesting, especially considering that the EU strives to go full electric on vehicles. Obviously, this could free major volumes land and therefore of food to feed the future. Just keep this number in your mind as an indicator but be careful to not extrapolate too quickly for the rest of my story because not all agricultural lands are as good as those used for crops in the EU and not all climates are as favorable.

Another similar comparison to make is to take a look at the USA. There, it is estimated that about 40% of the corn is used for the production of ethanol as a biofuel. If you take 40% of the area planted in corn, you get the size of two Irelands. Somehow ironically, this is also the size of the State of Iowa which is the top corn US state, and also for soybeans, 49% of which are used for biofuels. In the US, the ethanol mandate plays an important role for corn farmers. This is especially true since the US and China had a little disagreement during the first Trump administration, which resulted in China nearly buying no corn or soybean any longer from the US. This is still the case in 2025. The recent agreement on soybeans between China and the US might alleviate some of the pain but considering what a roller coaster this relationship is, let’s wait and see. US farmers cheered as the US recently increased volumes for the ethanol mandate. This is understandable, as US corn volumes have been quite high with about zero alternative market. It is actually to the point that the US is coming close to have a shortage of storage space for grain. Clearly, ethanol is not going to go away, unless the Midwest farmers decide to produce entirely different crops in the future. For water reasons, some have switched to sorghum as an alternative to corn for animal feed, but that goes only so far. Clearly, there will be little incentive to push too hard for electric vehicles as this would affect the domestic ethanol market. Without the ethanol market, it is not unreasonable to say that US crop farmers would all go bankrupt in a heartbeat. Even with the mandate, they are already in rough shape. This is the cost of losing your best customer. The old rule of thumb saying that it costs between 10 and 20 times more to lose a customer than to make some compromise sounds like it is still very relevant.

Of course, the EU and the US are not the only biofuel producers. There is more, like sugar cane ethanol in Brazil or even India making fast strides with bioethanol, but I will not include them in the calculation.

Anyway: about 2 Irelands with US corn ethanol.

Food waste

It is well known that about a third of all food produced is lost or wasted in some way. It is also true that most of the wasted food consists of crops. In developing countries, crops rot in the fields or in poor warehousing, or are eaten by vermin. In developed countries, the top two wasted products are bread and produce, both groups from plant origin, too. So, just for argument’s sake, let’s just consider that the food waste is just from arable land. Let’s forget the grasslands in this calculation. According to the UN FAO, the world arable land area is of about 1.38 billion hectares. A third of that is 460 million hectares, which is slightly more than the area of the EU as a whole, or slightly more than half the size of China or the US.

Expressed in Irelands, a third of the world arable land represents about 65 Irelands.

Warmer climate in Russia and Canada

Now, this is the fun part of the exercise. It is fun because 1) it is very speculative and 2) the result will blow your mind. Here is what I calculated: imagine a narrow strip of land of a width of 50 km across both Russia and Canada, which are both 9,000 km long from East to West. As summer are warming, it is not inconceivable that another 50 km to the North could be put in production for crops. These 50 km multiplied by two times 9,000 km is 900,000 km2 or 90 million hectares.

That narrow strips is roughly 20% of the EU area, or 13 Irelands.

Others

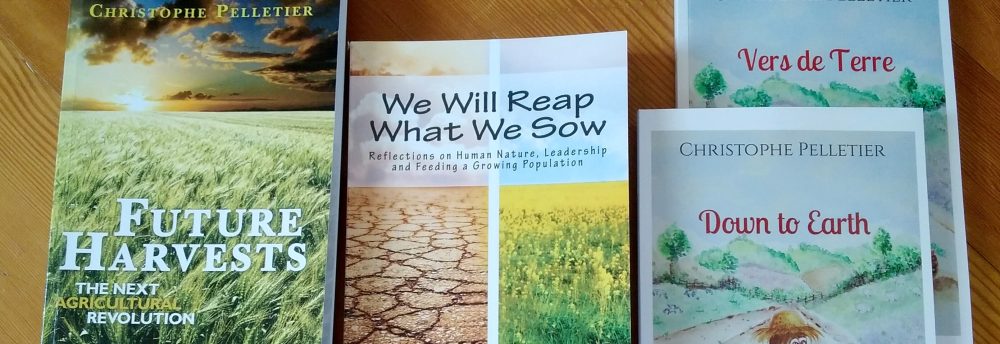

I will let you dig further where there is potential. Of course, there are challenges ahead. Climate change will also put yields under pressure. As I indicated, my purpose is mostly to make you think about whether the Earth is maxed out or whether we can still create of world of plenty. The answer will depend greatly on us and on our leaders. Do we want to cultivate the Earth for success or are we going to make pricey mistakes? That was the purpose of We Will Reap what We Sow, my second book, by the way.

Conclusion

This is a lot of Irelands!

Copyright 2025 – Christophe Pelletier – The Food Futurist – The Happy Future Group Consulting Ltd.

What will a higher price mean?

What will a higher price mean?